Commodity Markets

What is a Commodity?

A commodity is “a basic good used in commerce that is interchangeable with other goods of the same type.”1 Gold, barrels of oil and natural gas are all examples of commodities. Agricultural commodities include grains (i.e corn, wheat and rice), oilseeds (i.e. soybean and palm oil), livestock (i.e. cattle and pork), dairy (i.e. milk, butter and cheese) and fertilizer (i.e. Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium fertilizers). Because these goods are interchangeable, one bushel of commodity corn grown in Indiana, for example, is viewed and valued the same as if that bushel of commodity corn was from Iowa. This means all commodity corn can be pooled into one giant pot to sell and distribute.

The term “Commodity corn” is carefully used because not all grains, oilseeds, livestock and dairy goods are commodities. This is because commodity goods are not only interchangeable, they are most often used as raw material in the production of other finished goods and services.1 Take corn, for instance. Different corn seeds produce different types of corn. One type of corn is sweet corn, a food that can be directly consumed by humans. Dent corn, or field corn, is a type of corn that is high in starch, harvested dry and processed into a plethora of different products, such as animal feed, cornmeal, high fructose corn syrup, ethanol and even odor eliminators found in air freshener sprays (leading some, like Jason Wisniewski, to claim in this video that corn shouldn’t actually be viewed as food anymore). The latter, dent corn, is commodity corn, while sweet corn is not.

What is a Commodity Market?

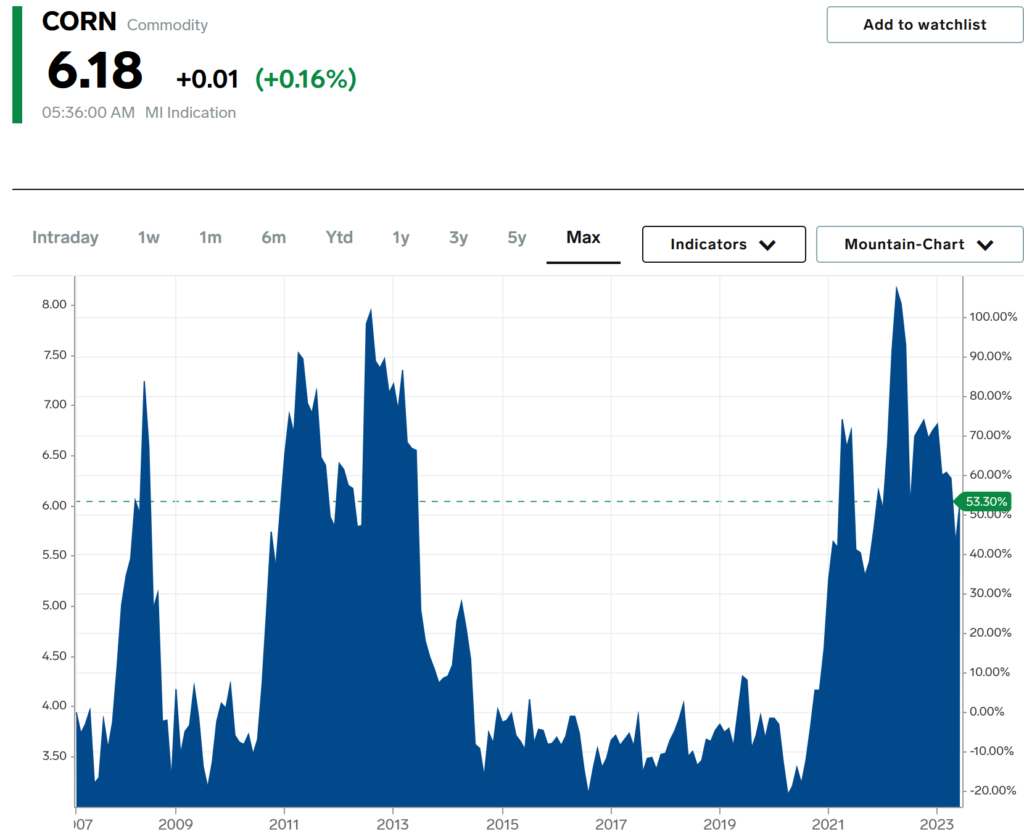

Commodity markets are basically where the physical value of a good, determined by supply and demand, is turned into a price on a piece of paper, which can be used to buy and sell contracts. This allows buyers and sellers to interact without the need to physically exchange the good. This means commodity farmers and ranchers are unable to set the price at which they sell their good, leaving much uncertainty as to what the price of their good will be worth in the future, given that droughts, floods, tariffs and even war can dramatically raise or lower prices in a short time. This volatility, as you can see by the unpredictable ups-and-downs of corn prices in the last 15+ years, has led to most commodity farmers and ranchers selling through “future contracts”.

Commodity markets calculate the future price of goods based on historical trends and current data, such as anticipated yield based on weather patterns. Farmers and ranchers are then able to sell contracts for their goods at a locked-in price long before their good is ready to be shipped off. Farmers and ranchers are considered “hedgers” because they are hedging their bets by locking in a certain price. Buyers are “speculators” because they are speculating that the commodity price will be higher at the time of the contract’s expiration compared to what they paid for the goods when they bought the contract.

How does this affect regenerative agriculture?

John F. Kennedy remarked over 60 years ago that, “The farmer is the only man in our economy who buys everything at retail, sells everything at wholesale, and pays the freight both ways.” While commodity markets do provide a known location to sell their goods, farmers and ranchers often receive the short end of the stick in this interaction because they are largely at the mercy of factors outside of their control. In addition, food travels more miles, exchanges hands and undergoes industrial processing more times before reaching dinner plates (or gas tanks or air fresheners…) than at any other time in history. Uncontrollable factors of the commodity market and increasing middlemen in the food chain are two main reasons why farmers only receive around 14 cents for every food dollar spent in the U.S.3

Regenerative agriculture seeks to decrease the uncontrollable factors to as few as possible. Even the idea that “you can’t do anything about the weather” is being challenged!4 One way to take control back is to reduce the need for costly fertilizer by increasing soil health and developing a more self-reliant ecosystem. Remember, fertilizers are priced on commodity markets, which determine prices largely by supply and demand. When, for example, corn prices are higher than average, many farmers plant commodity corn, thus increasing demand for nitrogen fertilizer. This increases the price of fertilizer and eats into profit from high corn prices. In addition, conflicts like the War in Ukraine can decrease supplies of nitrogen fertilizer, driving fertilizer prices further upward, leaving corn farmers with even less profit. Regenerative farmers and ranchers can mitigate, or even eliminate, the need for nitrogen fertilizer over time by unleashing the power of nitrogen-fixing and scavenging soil biology.

Regenerative farmers and ranchers can also mitigate risk by becoming price makers, not price takers. One example of price making is through the use of direct marketing. Public health awareness from the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing consumer awareness of ecologically and humanely raised food have led to increases in local food sales nationwide.6,7 Farmers and ranchers should see this as an opportunity to earn more of the food dollar by cutting out as many of the middlemen as possible and adding value to their own products.

There are benefits to selling into the commodity market, as mentioned before. However, playing the commodity market game is risky over time and gives a lot of influence to factors outside of the farmer or rancher’s control. Regenerative producers have learned that they don’t always have to play that game. They have liberated themselves to set more of the rules (and prices) of their new game.