Who Benefits the Most from Modern Ag?

Attitude of Gratitude

Every living creature on this planet eats because it takes energy and raw materials to grow, maintain and reproduce themselves. Humans are no exception, but the way in which we feed ourselves is a massive exception. No other species on the planet has figured out a food system quite like ours. Yes, plants technically “farm” microbes near their roots and some ants “farm” fungi in underground cities, but nothing compares to the season-defying, intercontinental food system that most humans enjoy today. The ability for the world to produce the quantity of food that it does and transport it thousands of miles before spoiling is truly a modern marvel of science and engineering. Most people, especially those of us in the developed world, should have some sense of gratitude for the abundance produced by this behemoth food system. After all, we live in an unprecedented time in human history in which so few people ever wonder where their next meal is coming from. That’s something to thankful for. And yet, serious questions exist concerning the ethics and sustainability of the current agricultural system.

The inconvenient truth is that producing, distributing and preparing food is big business, and schemers always appear wherever large quantities of money are to be had. This has certainly been true in other areas of the economy, like in the energy sector and the financial sector, so why would we expect the food sector to be any different? Maybe it’s because we all want our food coming from smiling farmers hand-delivering fresh vegetables, meat and dairy to their local communities. Or, thinking more broadly, it’s because feeding the world is an inherently altruistic endeavor. It makes sense, then, that individuals working in the space would be in it for the right reasons, right? There’s no doubt a large percentage of people working in the food sector do it for altruistic reasons, but it would be naive, and incorrect, to think that the current food system was designed, and is currently run, absent of schemers seeking personal gain from a basic human necessity. That’s a big claim that deserves big evidence. This article’s purpose is to provide such evidence by investigating how the industrialization of agriculture in the past couple centuries has affected various aspects within the modern food system. Namely, we will look at how the agricultural input industry, the producers and their communities, industries after the farm gate, the environment and public health have fared over that span of time. Particular attention will be given to the American agricultural system, but similarities can be found in other nations as they adopted industrial agricultural systems.

How Did We Get Here?

Before analyzing the last couple hundred years of ag, it’s necessary to take a brief journey through its complex and convoluted past to gain some all-important context. Most historians agree that modern agricultural practices began around the end of the last Ice Age (roughly 11,700 years ago) when various cultures across the planet began the process of domesticating plant and animal species.1 Our ancient ancestors expressed their latent capacity to shape wild landscapes and, in the process, learned they were no longer completely reliant upon the whims of nature for nourishment. This shift allowed communities to transition away from the nomadic lifestyle of hunting and gathering by learning how to produce a concentrated amount of food in one area of land. Towns, as well as specializations in art, politics, military, technology and economics, emerged and expanded as a consequence. More importantly, humanity’s relationship with the land changed in a dramatic way. Nature, at least partially, was now subservient to the desires of human civilization. This nature-shaping ethos has remained constant over the millennia, even though the exact methods of food production and distribution have changed drastically. Right, wrong or indifferent, this is the direction humanity took, and it’s what led us to where we are today.

This article will focus primarily on the last few hundred years of the food system, so for anyone wanting to dive deeper into the early history of agriculture, the following are great resources. First is the “Origin of Agriculture“, an entry from the Encyclopedia Britannica, and second is “The Oxford Handbook of Agricultural History” written by Jeannie Whayne.

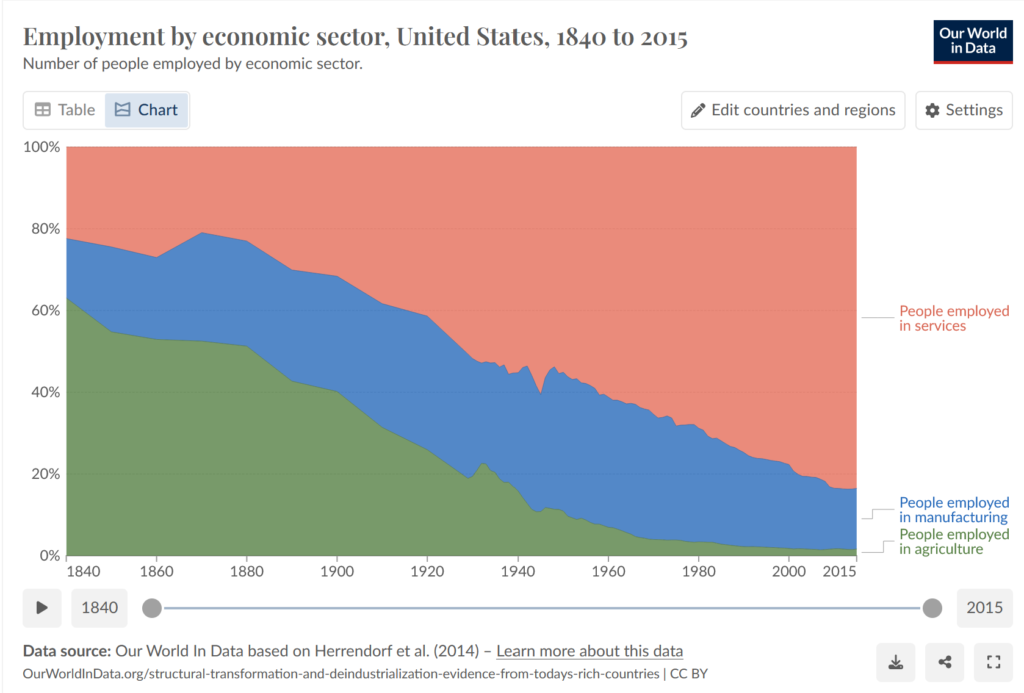

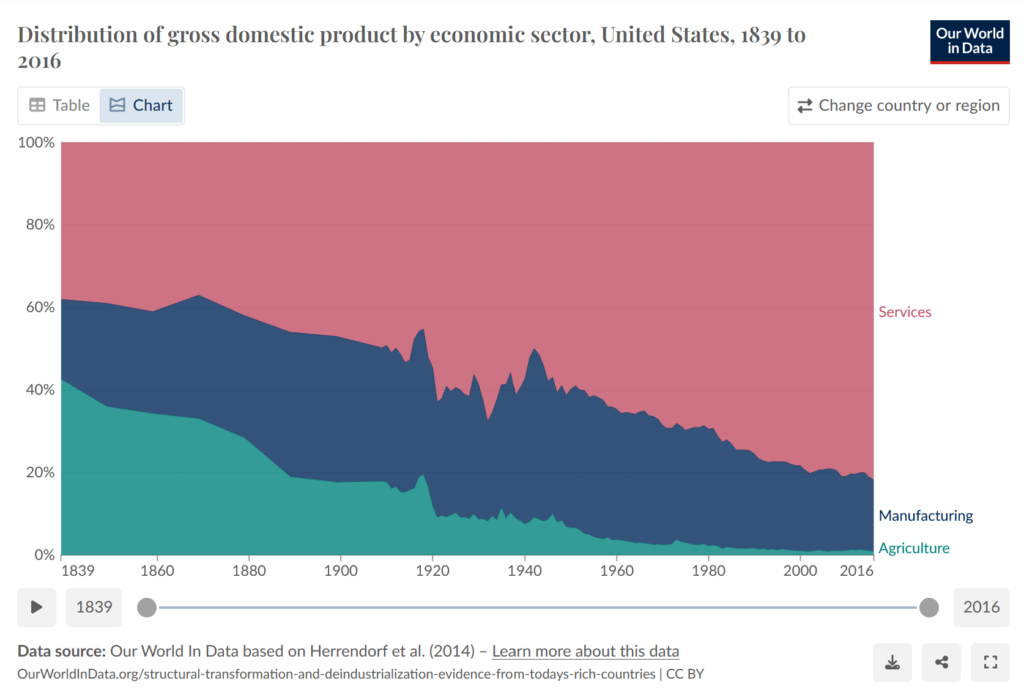

Innovations in technology and markets in the last 200 years or so are worth focusing on because they have advanced humanity’s ability to produce food and influence the landscape like no other time in history. Specifically, two revolutions are recognized during this period as providing the catalyst for global changes in agriculture. The first is the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries that brought technology like Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, Cyrus McCormick’s mechanical reaper, John Deere’s steel plow and the steam engine. In addition, advances in chemical fertilizers, grain elevators and access to railways greatly increased productivity and access to markets, particularly in the U.S., Great Britain and Canada. This upward tick in efficiency allowed more rural citizens to migrate into cities as fewer farmers were needed to manage the same area of land. Not only that, rural communities produced surplus quantities to feed these burgeoning cities filled with promising industrial jobs. This resulted in a push and pull of rural citizens to urban areas. The transition from an agrarian society to an industrial one is typically a slow process. In the case of the United States, it wasn’t until 1920 that more than 50 percent of the population lived in urban areas. Bear in mind that many people classified as “urban” at that time lived in towns with populations around 2,500-3,000!2

While the U.S. and Great Britain had become industrial economies by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many nations still operated agrarian-based economies at that time. These nations were especially vulnerable to the four horsemen of disease, pestilence, drought and flooding. Unfortunately, this meant living with the constant threat of famine. One example, among many, was Mexico in the 1940’s, where many fields of wheat were failing due to a disease called rust. Expert predictions pointed toward mass starvation. To prevent this catastrophe from happening, the Rockefeller Foundation’s Cooperative Mexican Agricultural Program was launched and Norman Borlaug, a budding young agricultural scientist at the time, headed south of the border. Borlaug and a team of others worked tirelessly to develop a disease-resistant wheat variety with a shorter stem. A short stem was desired because chemical fertilizer applications were producing wheat plants with seed heads too heavy for their lanky stems. Broken stems and drooping seed heads made it near impossible for wheat plants to grow properly or for them to be harvested efficiently. Borlaug and his team soon developed “dwarf” varieties of wheat that could hold up the weight of the bigger seed head and better withstand microbial disease pressure. Dwarf varieties drastically increased wheat production to the point where the Mexican economy became a net exporter of wheat in less than 20 years.3 News of this success story quickly spread around the globe and governments took notice, particularly Indian and Pakistani governments, who were trying desperately to prevent famine caused by rapid population growth. This prompted the call to Borlaug and his team. Borlaug agreed and began breeding plants to fit their southeast Asian context. After many tireless years of plant breeding, wheat yields increased by 60% in both nations, providing a much-needed boost in the fight against famine.4

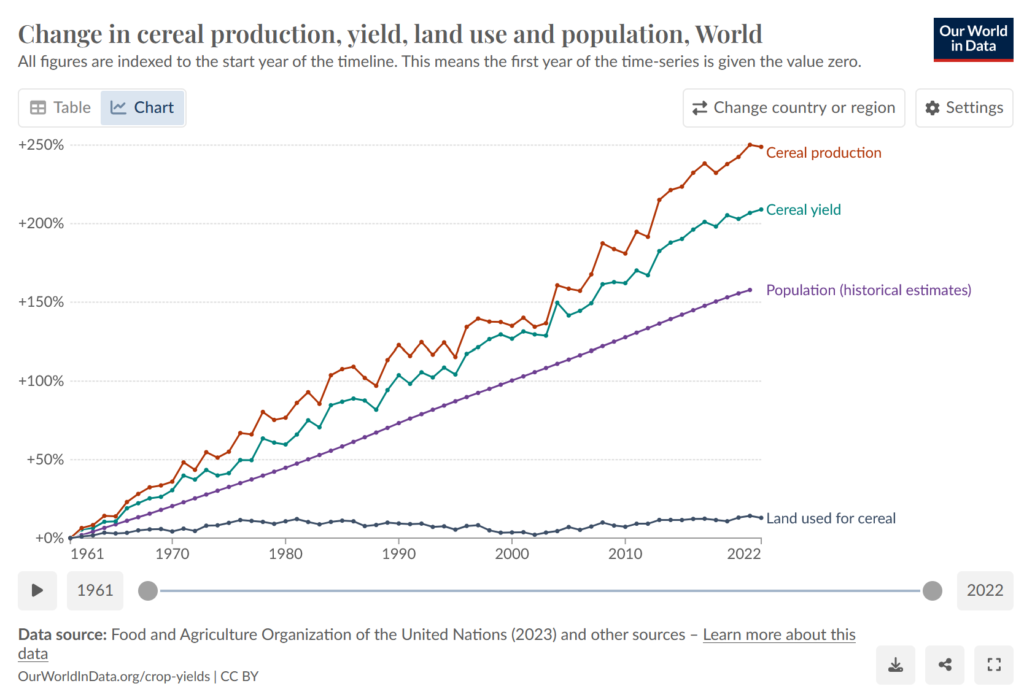

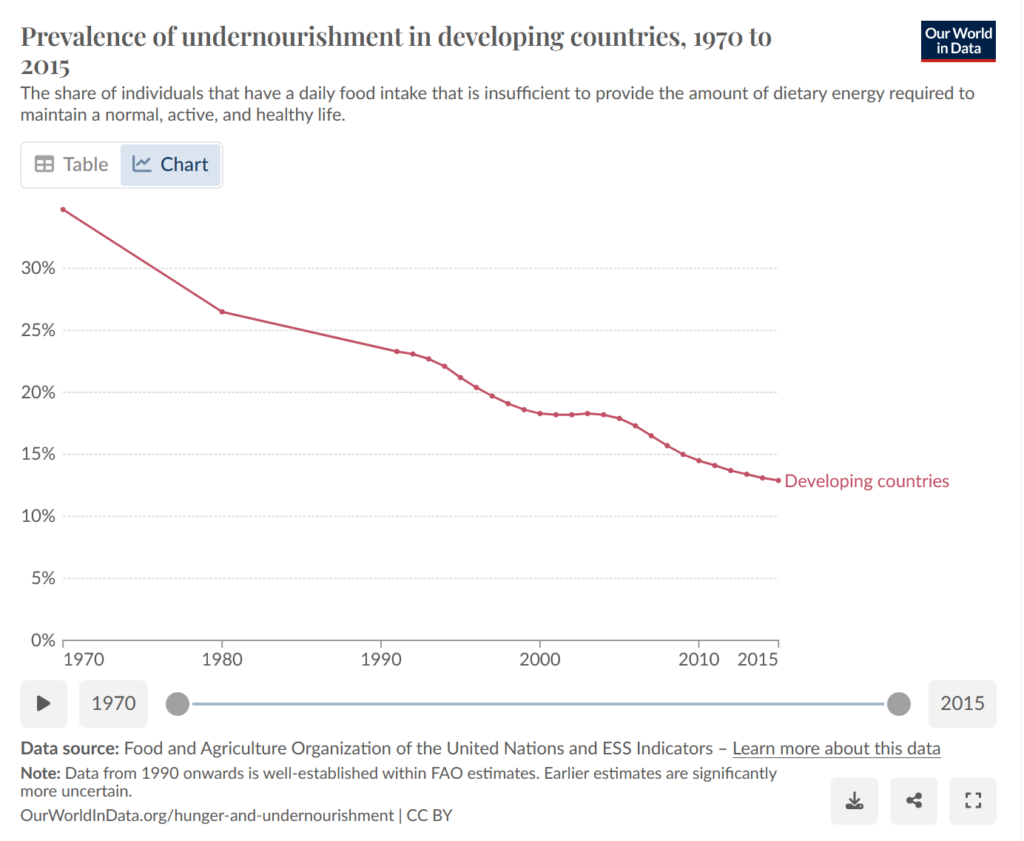

Producing more food on the same land can’t come out of thin air, though. Modern high-yielding varieties have large appetites for nutrients and the ability to protect themselves from broad spectrum disease and pest pressures is often unintentionally bred out. This necessitated a concurrent rise in the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides as new varieties were adopted. Despite the increased need for inputs, these varieties and the chemicals required to grow them were welcomed with open arms into the nations that had access and could afford them. The implementation of improved plant genetics, increased mechanization and high use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides of the mid-20th century was so widespread and influential that it has become known as the Green Revolution, the second of the two revolutions that dramatically shaped modern agriculture. Opinion is divided as to whether the Green Revolution was a net positive or negative, but one can’t deny the incredible impact it has had on modern society. In fact, it’s often said that the global adoption of Green Revolution technology has saved over a billion lives due to the significant increase in calorie production per agricultural acre. Once again, that’s something to be thankful for, especially from those who personally remember when the fear of famine hung over them like a perpetual dark cloud.

Adoption of the Green Revolution eventually set the stage for more of the world to transition away from agrarian economies. China, for instance, was able to start the transition once a more open economy and a change in agricultural policy paired with Green Revolution methodologies. This led to a massive increase in food production, which helped trigger a migration of workers to industrial centers, which then fueled its path to becoming a global industrial powerhouse in just 35 years.5 The near-miraculous transition of Brazil’s agricultural sector6 and India’s ongoing transition7 are also worth recognizing.

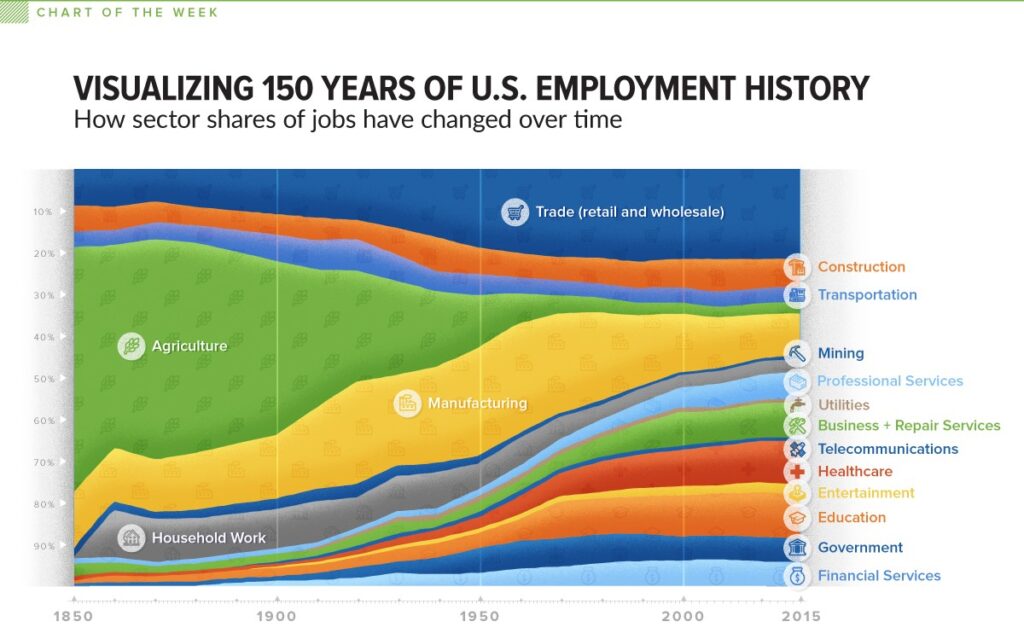

Interestingly, the industrial economy is only a stepping stone to the third and final transition of national economies, which occurs as jobs and GDP from the agricultural and manufacturing sectors are surpassed by the service industry. The United States economy from 1840 to 2015 is a classic example of this transition from an agrarian to a service economy. Thanks to this progress, only a little more than 1% of American jobs are in the agricultural sector, compared to 9% in Brazil, 25% in China, and 43% in India.8

Typically, this is the final message of any mainstream discourse on modern agriculture. Nature, and it’s pesky tendency to refuse bending to humanity’s will, has largely been tamed by modern science, technology and economics. When Nature steps out of line, we simply develop stronger methods to whip it back into shape. This progress, so the story goes, has consequently freed people from having to work in the primitive, depressing sector that is agriculture. Humanity has leveled-up and continues the march toward full separation from the natural order of this world. We are the master of our fate and the captain of our soul.

So we think.

Conventional Agriculture: Get Big or Get Out

To summarize the previous section, agriculture began nearly 12,000 years ago when humanity learned it could influence plants and animals in ways that allowed us to control food production. Modern agriculture is really the same old story, just on a much grander, industrialized stage. To illustrate this point, consider the words of Secretary of Ag William Jardine who said in 1927 that, “The United States has become great industrially largely through

mass production, which facilitates elimination of waste and lowering of overhead costs. Large-scale organization in the business world has affected tremendous economies both in production and distribution, and has enabled manufacturers to supply consumers with what they want when they want it. It seems to me that in this matter agriculture must follow the example of industry. It must have a similar and larger scale development of its business organization managed by competent executives.”9,10 Agricultural economist E.G. Nourse echoed these sentiments by claiming, “the essential features of economic organization which have brought efficiency into industrial pursuits must be incorporated into agriculture or else it must remain the slow and backward brother in the family group of our economic life.”9 Last but not least, agricultural engineer Raymond Olney announced that, “No one will object

to calling a farm a factory. It is a factory. The soil and seed are the raw materials, and from these are manufactured a variety of finished products, through the agencies of sun, air, moisture, power, and implements. The finished products of the farm factory are cereal, forest, vegetable, and fruit crops, and livestock and livestock products, are they not?”9

Driven by the attitudes of Jardine, Nourse, Olney and many others, agriculture in the United States was transitioning into an industrial practice throughout the first half of the 20th century. This transition was happening at a fair pace, no doubt, but policy changes in the 1970’s sent the change into overdrive. Earl “Rusty” Butz , former secretary of agriculture in the Nixon and Ford administrations, is often attributed as the person most responsible for catalyzing the modern industrial mindset in American agriculture. Butz entered his position as secretary of ag at a time when the US government enforced caps on grain production for the purpose of mitigating the risk of overproduction, which would depress prices. Farmers were paid to leave land out of production when data showed there was a heightened risk of oversupply. Land would go back into production as supply dropped and prices rose. Butz did not support these production caps. His idea was to unchain the American farmer from obvious government overreach so they could achieve maximum output. To assuage the fear that lifting restrictions wouldn’t lead to Depression-era overproduction, low prices and farm foreclosures, Butz promised that the US government would broker deals with the global market to sell the surplus.11 This solution persuaded enough politicians to jump on board, and the repeal of production caps was included in the Farm Bill of 1973. Butz announced the win by saying, “With the new Farm Act, we have experienced a 180-degree turn in the philosophy of our farm programs. We’ve abandoned the longtime philosophy of curtailment and cutback to the new philosophy of expansion. We’re going to see the most massive increase in production of farm products ever in the history of this country.”12 Farmers were urged to partake in this new philosophy of expansion by “planting from fence row to fence row“, which would ensure every acre of farmland was given the chance to maximize production.

Butz and Nixon’s new agricultural policy led to an immediate drop in US grain supplies due in large part to mass exports of surplus to the Soviet Union. This had the effect of raising grain prices for the American farmer. As a result, millions of Midwestern farmers spent the 1970s “taking on debt to buy more land, bigger and more complicated machines, new seed varieties, more fertilizers and pesticides, and generally producing as much as they possibly could.”13 Unfortunately, the good times didn’t keep rolling. Soviet purchases of grain slowed down, and U.S. grain supplies increased as the decade came to a close. The 1980’s ushered in a period of depressed prices due to oversupply, as well as high interest rates on skyrocketing debt, leading to thousands upon thousands of farm foreclosures.14 “Get big or get out”, a phrase championed by Butz, was in full swing. Eventually, the Farm Bill of 1985 brought about policy to stop the bleeding, but serious damage had already been done to rural America. Those that had “gone big” lived on, while many of the rest were forced to “get out”.

The morality of such a system is up for debate, but one thing is for certain: “Economies of scale” was now the name of the game. Agriculture had become a race to the bottom to see who could produce the most at the lowest cost, just like any other industrial product. Oftentimes, the term “conventional agriculture” is used to describe this modern system of farming at scale. One insightful definition of conventional agriculture can be found in the Essentials of Environmental Science textbook. Author Kamala Drosner writes that, “Conventional farming systems vary from farm to farm and from country to country. However, they share many characteristics such as rapid technological innovation, large capital investments in equipment and technology, large-scale farms, single crops (a.k.a. monocultures); uniform high-yield hybrid crops, dependency on agribusiness, mechanization of farm work, and extensive use of pesticides, fertilizers, and herbicides. In the case of livestock, most production comes from systems where animals are highly concentrated and confined.”15 For better or worse, the adoption of conventional agriculture has turned agriculture, traditionally diversified and region-specific, into an increasingly homogenized, globalized and industrialized process.

Now that a way-too-brief overview of the modern agricultural system is out of the way, it’s time to get to the meat and potatoes of the issue at hand. The following sections will detail which sectors of the agricultural economy have benefited the most during this shift from agriculture to agribusiness. The goal is not to demonize anyone or any system. After all, humanity has long searched for systems that could stave off starvation through ample food production. Modern science, technology and industry have done an incredible job of accomplishing this task to sufficiently feed the world’s population. This is worth acknowledging and praising, in my opinion, even if there have been bad actors influencing the direction along the way. Rather, the goal of the following sections is to elucidate how various sectors have fared during the industrialization of agriculture. This includes 1) the agricultural input industry, 2) farmers and rural communities, 3) industry like supermarkets and restaurants that purchase agricultural products, 4) the environment and 5) public health. Hopefully this will inspire policymakers, consumers and farmers alike to consider all aspects of society when participating in future agricultural systems.

Agricultural Input Businesses

Farmers in centuries past typically worked on small-sized plots with team animals, a couple implements, seeds and livestock. Many of those inputs were produced and/or reared by the farmer. Now, a typical conventional row crop farmer needs to rent or purchase an enormous tract of land, a tractor or two, a combine harvester, various implements, a grain cart, tools to repair their equipment, a shop to work on their equipment, a mechanic to repair what they can’t, fertilizer, pesticides, seeds, irrigation systems, bins to hold their grain, trucks to haul the grain to the buyer and energy in the form of diesel and electricity to run their equipment. Much of the same goes for modern livestock producers, with the addition of pharmaceutical products, haying equipment, supplemental feed and facilities to hold, handle and milk livestock. Every single one of these inputs costs the farmer or rancher money, so it’s easy to see just how lucrative the agricultural input industry can be given the sheer quantity of stuff farmers are told they need to purchase in order to be successful.

One input worth investigating is the agricultural machinery industry. As is the case with most industries, market concentration has resulted in a few large corporations dominating this space. In 1921, there were 186 different companies vying for space in the tractor market and hundreds of others producing farm equipment. Now, barely a dozen major companies produce farm equipment for the United States market, with about 5 players dominating the space. (https://www.agdaily.com/lifestyle/evolution-of-farming-a-new-look-at-old-traditions/,https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/united-states-agricultural-tractor-machinery-market ) It’s hard to imagine given today’s omnipresence of tractors and combines, but only about 600 tractors were in use in 1907 in America. That number grew to almost 3.4 million by 1950. (https://www.britannica.com/topic/agriculture/Scientific-agriculture-the-20th-century) Today, there are an estimated 4.4 million tractors in use in America and over 25 million worldwide. (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.AGR.TRAC.NO)

As a result of this rise in demand, individual companies and their executives in this highly consolidated space are experiencing unprecedented financial success. For example, John Deere net income has increased from $2.8 Billion in 2011 to $10.1 Billion in 2023 (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/DE/deere/net-income) These gains aren’t without their challenges, as John Deere has recently (July 2024) laid off employees in Illinois and Iowa and will move the production of skid steer loaders and compact track loaders from its Dubuque, Iowa facility to Mexico by the end of 2026 due to inflation and decreased demand. (https://finance.yahoo.com/news/john-deere-announces-mass-layoffs-172937300.html) Still, John Deere has done well enough for Chairman, Chief Executive Officer, and President at DEERE & CO, John C. May to make $26,285,804 in total compensation for the fiscal year 2023. Of this total $1,591,674 was received as a salary, $5,911,159 was received as a bonus, $5,733,640 was received in stock options, $12,446,367 was awarded as stock and $602,964 came from other types of compensation. (https://www1.salary.com/John-C-May-Salary-Bonus-Stock-Options-for-DEERE-and-CO.html) AGCO corporation, another American corporation, has seen annual net income skyrocket from $136 million in 2009 to $1.2 billion in 2023. (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/AGCO/agco/net-income) As Chairman, President & CEO at AGCO CORP, Eric P. Hansotia made $14,704,086 in total compensation. Of this total $1,316,667 was received as a salary, $3,732,750 was received as a bonus, $0 was received in stock options, $9,252,255 was awarded as stock and $402,414 came from other types of compensation. (https://www1.salary.com/Eric-P-Hansotia-Salary-Bonus-Stock-Options-for-AGCO-CORP.html) Internationally, CNH equpiment and services raised net profits from $677 million in 2013 to $2.3 billion in 2023. (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/CNH/cnh-industrial/net-income) German agricultural machinery company Claas reported profits of €347.1 million in 2023, up 259% from 2022. (https://annualreport.claas.com/2023/index_en.html) Many companies in this space bring in revenue from sources other than ag equipment, such as John Deere’s financial services offered to farmers and ranchers. (https://www.wsj.com/articles/americas-farmers-turn-to-bank-of-john-deere-1500398960)

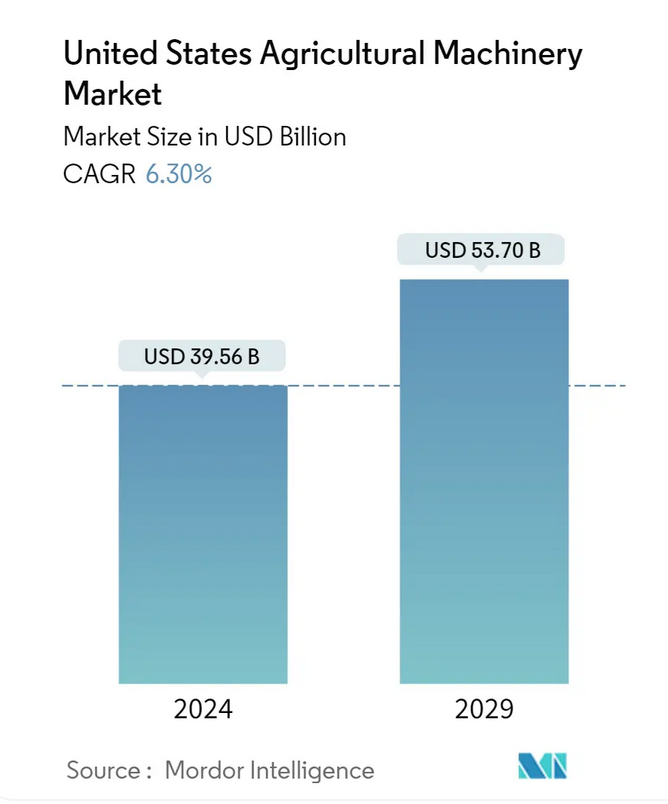

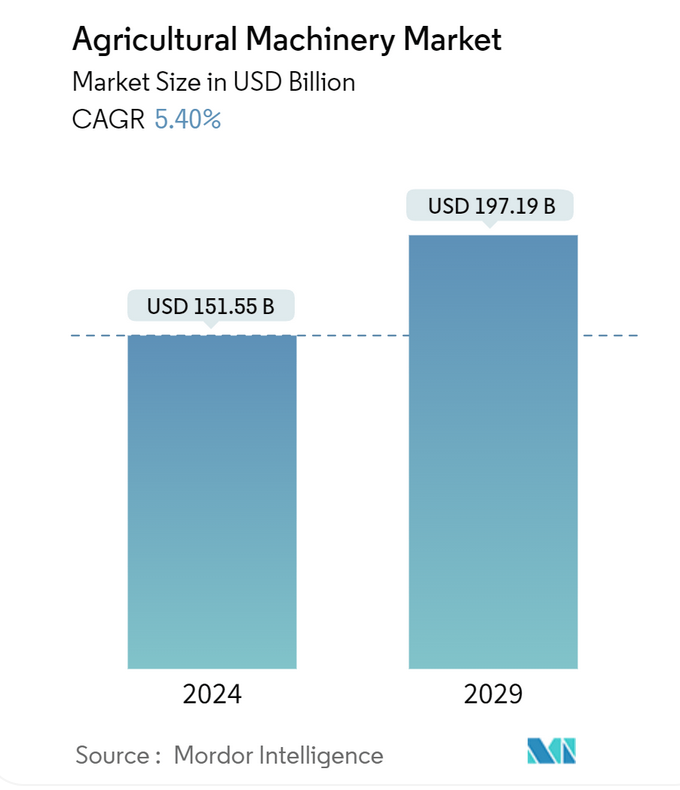

To ease fears that successful corporations have been cherry-picked to prove a biased agenda, let’s take a look at the ag equipment market as a whole. According to Mordor Intelligence, a market analyst group, the agricultural machinery market is reaching new heights of financial success. They report that, “The United States Agricultural Machinery Market size is estimated at USD 39.56 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach USD 53.70 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) of 6.30% during the forecast period (2024-2029).”( https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/united-states-agricultural-machinery-market) Worldwide, the Agricultural Machinery Market size is estimated at USD 151.55 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach USD 197.19 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 5.40% during the forecast period (2024-2029). Source: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/agricultural-machinery-market) Increased labor costs and increased average farm size make farmers adopt agricultural machinery in farming, fueling the market growth studied during the forecast period. (https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/united-states-agricultural-machinery-market)

Two lucrative agricultural inputs often looped together are the agrochemical and seed industry. Agrochemicals are “any chemical used in agriculture, including chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides. Most are mixtures of two or more chemicals; active ingredients provide the desired effects, and inert ingredients stabilize or preserve the active ingredients or aid in application.” (https://www.britannica.com/technology/agrochemical)

Arguably the most influential agrochemical is fertilizer. Farmers have been fertilizer their fields for centuries with organic fertilizers like compost and manure. In fact, bird manure, called guano, off the coast of Peru was all the rage in the 19th century as a rich source of phosphorus until the source was quickly mined out and supply dwindled. (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-gold-rush-led-real-riches-bird-poop-180957970/) Today, most fertilizers applied to farms and ranchers are synthetic, meaning they are processed and packaged in a factory in an inorganic form. The best example of this process is the Haber-Bosch process. Living things require a large quantity of nitrogen atoms to build their proteins and genetic material. Fortunately, everyone above ground is literally swimming in the stuff, as 78% of air is composed of nitrogen. Unfortunately, these nitrogen atoms are so tightly paired to each other that they are essentially unusable for biological purposes. Only a select few processes are able to separate this triple-bonded “dinitrogen” molecule and put each nitrogen atom in a form that life can eventually use, like ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3-). Lightning is one such process that contains enough energy to unlock dinitrogen. Another is through the interaction of dinitrogen and a microbially produced enzyme called nitrogenase. For centuries, farmers had no way of applying nitrogen to agricultural crops outside of applying slow-release manure and compost, as well as growing legume plants. Legumes team up with nitrogenase producing microbes by providing them food and shelter in the form of root nodules in exchange for nitrogen that has been “fixed” into a usable form. It wasn’t until 1908 when German scientist Fritz Haber filed his patent on the “synthesis of ammonia from its elements”. In other words, he had discovered a mechanical process to separate dinitrogen out of the air.(https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo325) Another German, Carl Bosch, later designed a high pressure, high temperature system that effectively and economically scaled up industrial nitrogen fixation. In fact, the reaction is carried out at pressures ranging from 200 to 400 atmospheres and at temperatures ranging from 400° to 650° C (750° to 1200° F).”(https://www.britannica.com/technology/Haber-Bosch-process) (It’s kind of crazy that little microbes can do this by themselves, isn’t it?) To honor the two men, the industrial separation of dinitrogen is called the “Haber-Bosch Process.”

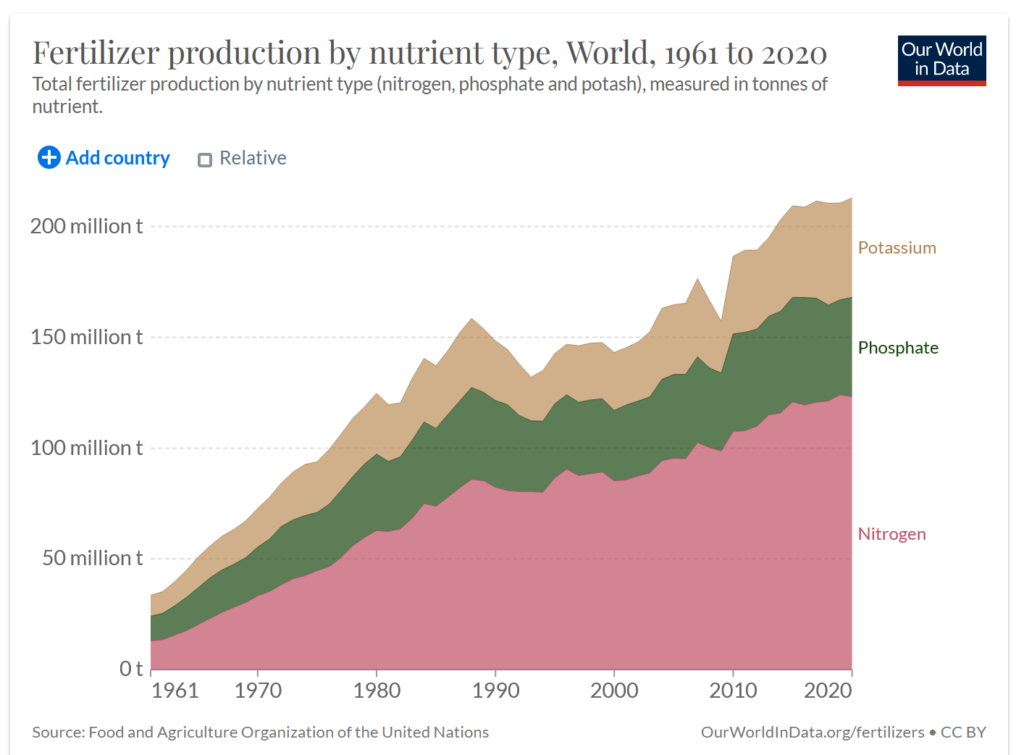

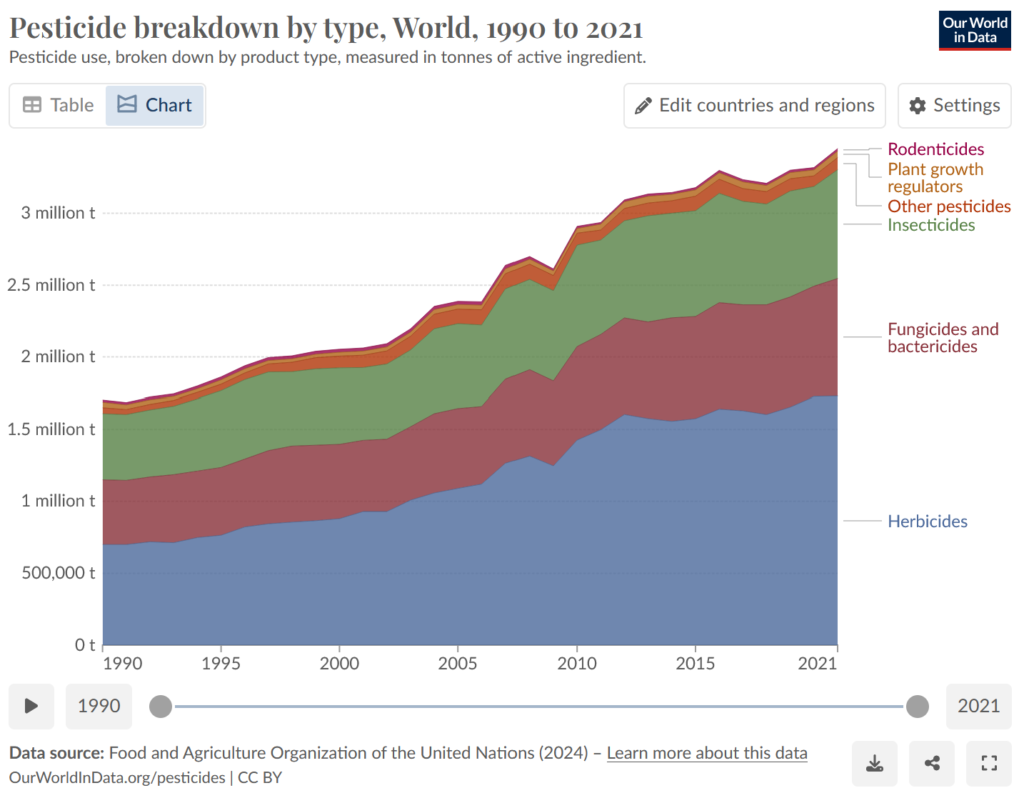

A large quantity of industrially produced nitrogen was originally used as an ingredient in munitions during military conflicts in the first half of the 20th century. Unfortunately for nitrogen factories, World War II eventually came to a close, and nitrogen supplies needed to be sold elsewhere. These companies turned their attention to farmers, which worked like a charm. Post-World War II sales of nitrogen fertilizer rose dramatically as farmers observed with their own eyes the quick growth and deep greening of their crops and forage. Production and sales of nutrients that need to be mined and refined like phosphorus and potassium also skyrocketed throughout the 20th century thanks to mass adoption of Green Revolution methodologies. Finally, pesticide use also rose significantly during that period as more farmers adopted intense, monoculture production systems.

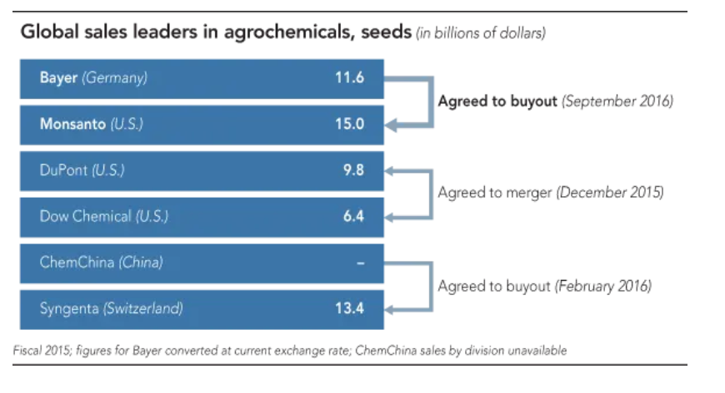

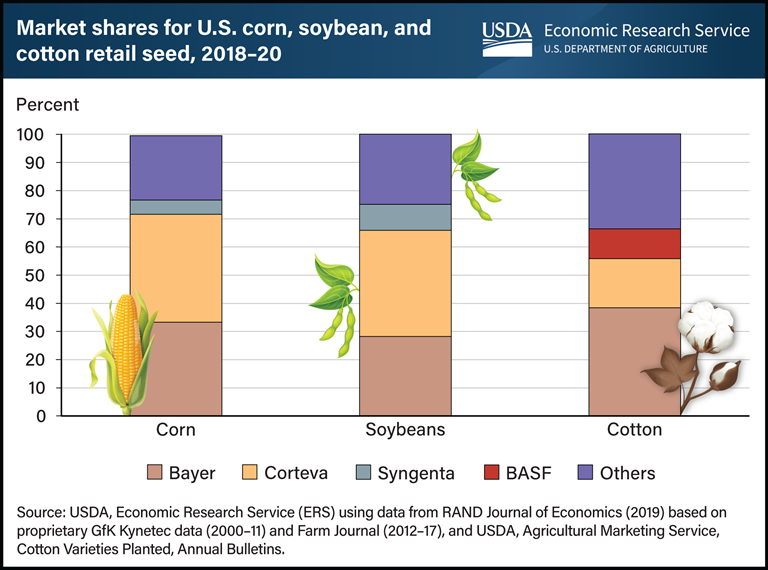

Needless to say, companies are making beaucoup bucks off of these agrochemical sales. That makes sense, but what many people may not know is that only a select few companies produce and sell the majority of agrochemical products that sustain modern agriculture. Acquisitions and mergers in the past few decades have left this space even more consolidated, the “Big Six” recently became the “Big Four”. Dow and DuPont merged to become Dow DuPont in 2015 (later becoming Coretva Agriscience), ChemChina acquired Syngenta in 2016 and Bayer acquired Monsanto in 2016. These three agribusiness mergers alone have concentrated control in the agrochemical/seed market into the hands of an oligarchy comprised of Bayer, BASF, Corteva, and Chem-China, providing them with the ability to exert an enormous amount of influence on the agrochemical and seed industry. (https://www.ocf.berkeley.edu/~prb/the-big-six-to-the-big-four-the-rise-of-the-seed-and-agrochemical-oligopoly/) For example, Bayer and Corteva now control approximately 70% of the corn and soybean seed market in the U.S., a significant increase from around 40% two decades ago, according to USDA data. (https://www.agweb.com/news/business/taxes-and-finance/corteva-now-beating-out-bayer-companys-market-share-surges-soybeans) As a farmer or rancher, does this consolidation of power and influence make you feel more or less confident in the free market to set fair prices for your chemicals and seed?

Financially, the Big Four are doing very well. In 2023, Bayer’s gross profits were $30.1 billion (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/BAYRY/bayer/gross-profit), BASF’s were $18.0 billion (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/BASFY/basf-se/gross-profit) and Corteva’s were $7.3 billion (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/CTVA/corteva/gross-profit). At the time of writing, BASF is seeing revenue fall in 2024 as high energy prices have hurt sales and profit.(https://www.ft.com/content/4e8699a2-dd69-489e-a1b9-543000109957) Another agrochemical giant, Bayer, reports their Crop Science arm saw a”significant decline in sales and earnings against very strong prior year, mainly due to lower glyphosate prices.” (https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/2024-03/bayer-annual-report-2023.pdf) Finally, Corteva Agriscience sales and profits have also been underwhelming (https://www.corteva.com/content/dam/dpagco/corteva/global/corporate/files/press-releases/01.31.2024_4Q_2023_Earnings_Release_Graphic_Version_Final.pdf). Corteva appears to be weathering the storm well, however, as Chief Executive Officer at CORTEVA INC, Charles V. Magro made $13,234,872 in total compensation in 2023. Of this total $1,341,923 was received as a salary, $1,472,175 was received as a bonus, $2,050,001 was received in stock options, $8,200,042 was awarded as stock and $170,731 came from other types of compensation. (https://www1.salary.com/Charles-V-Magro-Salary-Bonus-Stock-Options-for-Corteva-Inc.html) Many more of their executives make well over $1 million annually as well.

Corporations that specialize in fertilizer production also appear to be thriving financially. Nutrien, the largest soft rock miner and potash producer in the world and North America’s second largest phosphate producer, recorded over $1 billion in net income for 2023 and over $7.6 billion in net income in 2022. (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/NTR/nutrien/gross-profit) The Mosaic Company, a Fortune 500 company based in Tampa, Florida which mines phosphate, potash, and collects urea for fertilizer, brought in a net income of $1.1 billion in 2023 and $3.5 billion in 2022. (https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/MOS/mosaic/net-income)

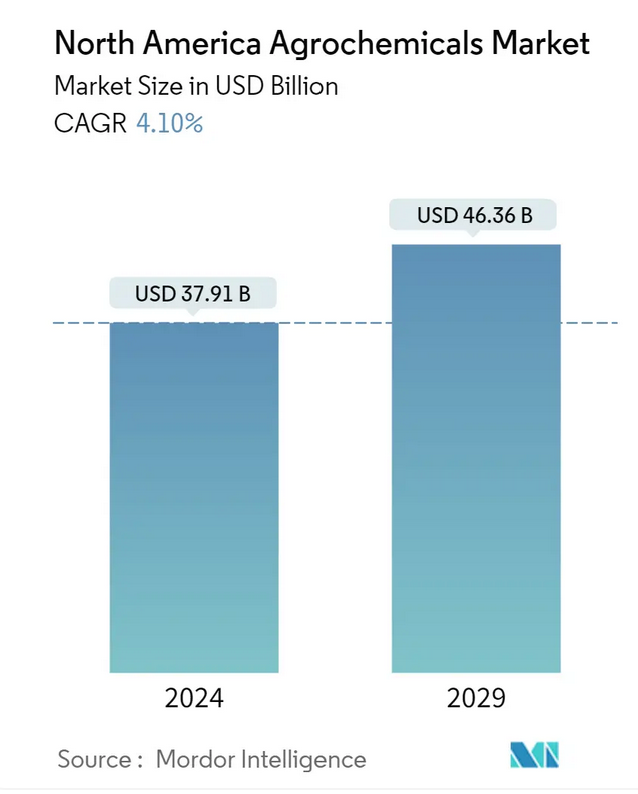

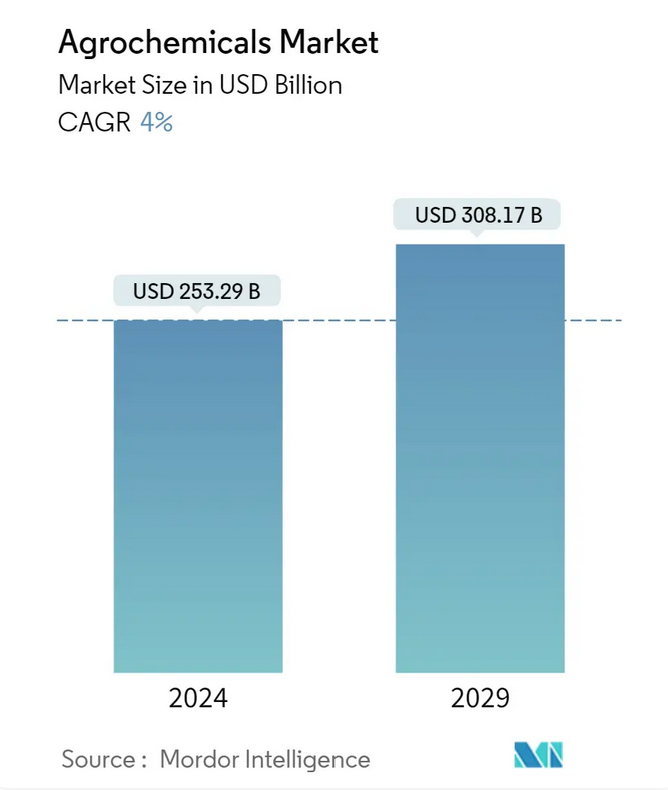

On the whole, it appears that agrochemical and seed sales won’t be slowing down anytime soon. Mordor Intelligence writes that, “The North America Agrochemicals Market size is estimated at USD 37.91 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach USD 46.36 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 4.10% during the forecast period (2024-2029).” (https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/north-america-agrochemicals-market) Globally, “the Agrochemicals Market size is estimated at USD 253.29 billion in 2024, and is expected to reach USD 308.17 billion by 2029, growing at a CAGR of 4% during the forecast period (2024-2029).” (https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/agrochemicals-market) Many, if not most, farming and ranching ecosystems have become so degraded that they now rely on these inputs to keep them productive, meaning that abatement of chemical use is not advised in most cases. Ecosystems need to be weaned off of them just as a person with addictions to certain substances need to be weaned off slowly to avoid severe withdrawal symptoms. Sri Lanka’s massive organic movement failure is evidence of what can go wrong when inputs are forbidden basically overnight. Unfortunately, not many large-scale producers have begun this transition away from high input use, which means sales of agrochemical products

will only increase as land is pushed harder to produce enough food for a growing world population.

Finally, fossil fuels are an extremely important input for modern day farmers and ranchers. Whether it’s natural gas used to separate nitrogen fertilizer ) or diesel fuel used to power heavy equipment, fossil fuels are currently the lifeblood of conventional agriculture, and consequently all of society. In 2022, American farms spent nearly $18 billion dollars in fuel costs (https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Farm_Production_Expenditures/arms3cht7.php).

Farmers & Ranchers

The previous section illustrated that the industry dedicated to selling products to farmers and ranchers is doing pretty well economically. Let’s now turn our attention to the farms and ranches buying their products. Are these businesses also faring well in the current industrial agricultural system? What about rural life in general? Are farmers, ranchers and their communities experiencing a golden age of health and wealth? The answer to these questions, as always, is complicated. One thing for certain is that the number of farms, ranches and workers on these operations has continually shrunk in the past two centuries, even as national populations have risen dramatically. If there’s one theme running through this whole article it’s that consolidation and concentration have taken hold of agriculture all along the chain. This is the natural outcome of an industry that chooses to operate by the economies of scale model, so it should come as no surprise to anyone what’s happened. Whether this is a good or bad result is up to you to decide.

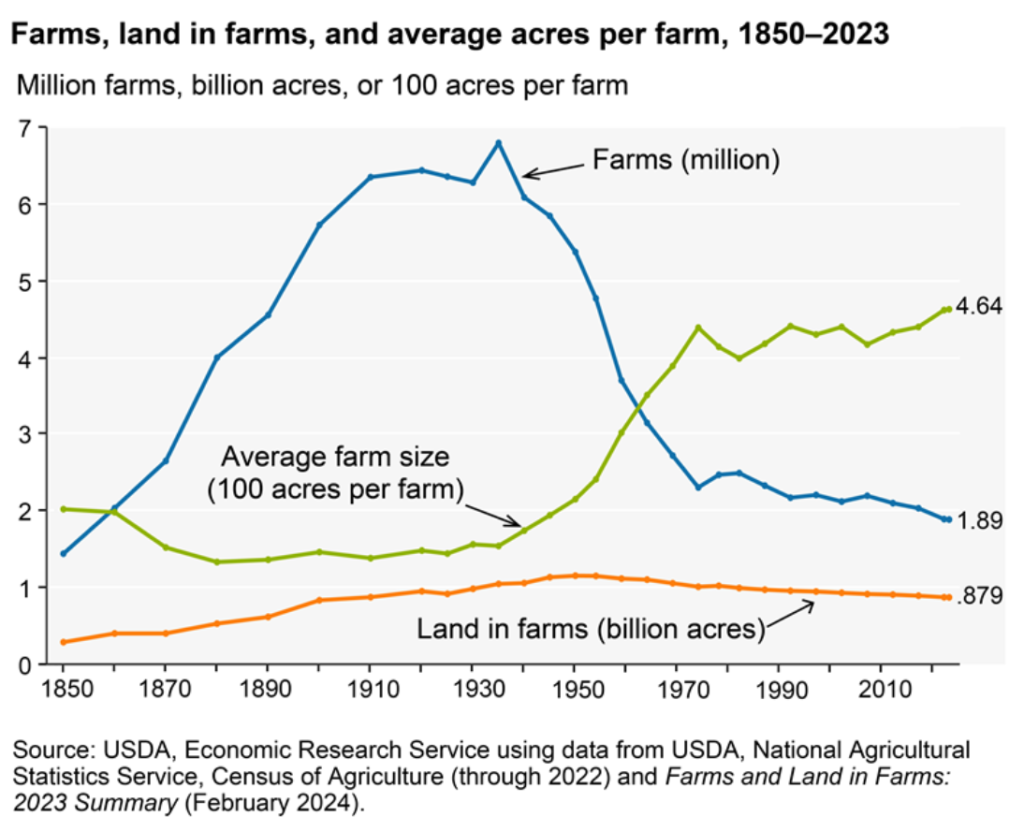

According to the USDA, the number of American farms peaked at 6.8 million farms in 1935, at which point it began to decline sharply until the early 1970s. The number of farms decreased during this period primarily due to growing productivity and increased non-farm employment opportunities. Since 1982, the number of American farms has dropped much more slowly than the period from 1935-1975. The most recent USDA survey indicates the number of farms is still shrinking, as there were 1.89 million U.S. farms in 2023, which is down 7% from the 2.04 million reported in the 2017 Census of Agriculture. Similarly, the amount of land used for agriculture follows a downward trend. Total farmland decreased from 900 million acres in 2017 to 879 million acres in 2023. (https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/9-3-conventional-agriculture/) This is partially due to urban and suburban sprawl swallowing up productive farmland. In fact, since 1970, over 30 million acres have been lost to development.

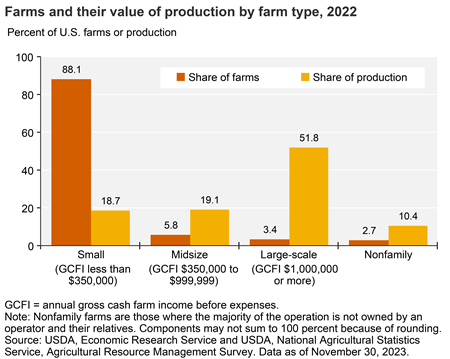

While the number of farms has decreased, the size of the remaining farms has increased. The USDA writes that, “Cropland has been shifting to larger farms. The shifts have been large, centered on a doubling of farm size over 20-25 years, and they have been ubiquitous across States and commodities. But the shifts have also been complex, with land and production shifting primarily from mid-size commercial farming operations to larger farms, while the count of very small farms increases.” (https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/45108/39359_err152.pdf?v=7180.1) Livestock operations have also shifted toward higher concentrations of animals per farm, especially for the hog and dairy industry. (https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44292/13804_eib43b_1_.pdf?v=7781) Census data shows that the average farm size was 464 acres in 2023, which is up 5% (441 acres) from 2017. (https://www.reuters.com/world/us/number-us-farms-falls-size-increases-census-shows-2024-02-13/). Given that mid-sized farms are making way for increasingly large farms while the number of small farms increases, the minor increase in average farm size is likely deceivingly small. A more important statistic is that the proportion of productivity from large-scale farms has increased greatly in recent decades. Since 1990, small and medium-sized farms have gone from producing nearly half of all agricultural products in the US to around a third in the 2020’s. (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/farming-and-farm-income/). Currently, the USDA estimates that the 105,384 farms with sales of $1 million or more sold more than three-fourths of all agricultural products and accounted for 85% of the market value of agricultural production. (https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2010/05/18/small-farms-big-differences) (https://www.nass.usda.gov/Newsroom/2024/02-13-2024.php) Models show that global trends will likely follow the same path as more nations adopt economies of scale agriculture, with one estimating the number of farms decreasing “from the current 616 million (95% CI: 495–779 million) in 2020 to 272 million (95% CI: 200–377 million) by the end of the twenty-first century, with average farm size doubling.” (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-023-01110-y)

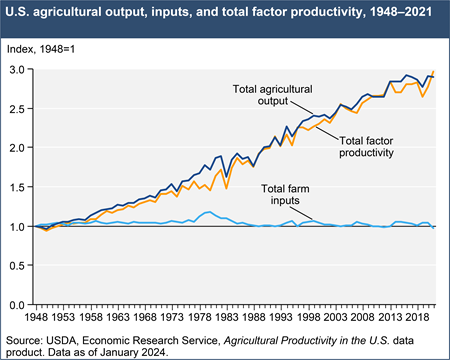

Miraculously, total farm production nearly tripled between 1948 and 2017, even as the number of farms, farmland and farm labor declined. The USDA states that the growth in farm output is “largely due to innovations in animal and crop genetics, chemicals, equipment and farm organization.” (https://www.usda.gov/media/blog/2020/03/05/look-agricultural-productivity-growth-united-states-1948-2017) Globally, agriculture has experienced a similar upward trend in productivity and it’s estimated that between 70% and 90% of the recent increases in food production are the result of the adoption of conventional agriculture rather than greater acreage under cultivation. (https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/9-3-conventional-agriculture/)

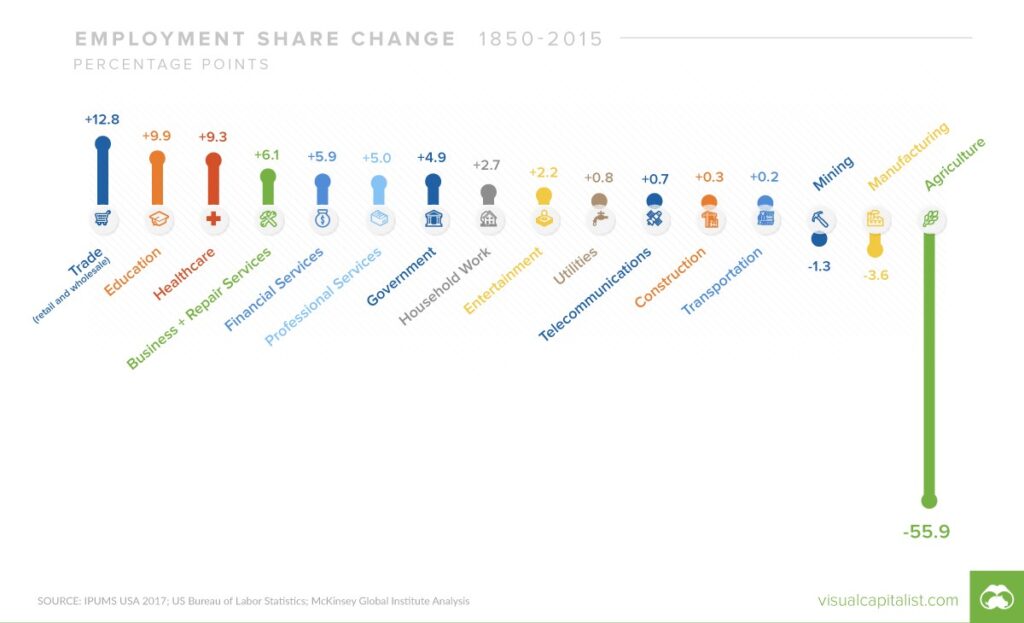

Consolidation of farms also means that fewer Americans are working in the agricultural sector. Changes in U.S. jobs by sector from 1850-2015 reveals that the employment share of agricultural jobs has fallen by 56% during that time. (https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-150-years-of-u-s-employment-history/) From 1960 to 2022 alone, agricultural jobs have gone from making up 8.3% of all American jobs to 1.6% in 2022. (https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/employment-in-agriculture-percent-of-total-employment-wb-data.html) Future outlook for agricultural jobs shows that this downward trend won’t change direction anytime soon. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of agricultural jobs is set to decline an additional 2% during the ten-year period between 2022-2032. (https://www.bls.gov/ooh/Farming-Fishing-and-Forestry/Agricultural-workers.htm)

Globally, the percentage of employees working in agriculture is dropping quickly as well. In 1991, 43% of employees worldwide worked in agriculture in some form or fashion. Today, that number has dropped to 23%. (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.AGR.EMPL.ZS) A full list of nations and their employment numbers can be viewed here, courtesy of the World Bank.

The decrease in farms and agricultural jobs isn’t necessarily a good or bad outcome. After all, statistics cannot imply “good” and “bad”. What they show is simply the direction most of the world’s economies have chosen, and fair enough to them. Promises of food security and material wealth made by conventional agricultural systems are hard to turn down, especially when the system does result in a massive increase in output. There’s also something to be said for creating a system that provides more individuals with the freedom to choose a career path outside of subsistence farming. It’s likely that the job you currently hold was chosen because it interested you, not because you had to produce immediate basic needs for you and your family. That’s something to be thankful for.

Even so, it’s probably worth asking how many millions of farmers and farming families were happy that their businesses didn’t survive the transition to industrial agriculture. Farming isn’t everyone’s passion, of course, and many families were undoubtedly excited to find new lives in cities and towns that offered the prospect of well-paying industrial and service-based jobs. However, it’s also true that there existed many passionate farmers who were forced off of land that their families had farmed for generations because they could not adapt to the changing agricultural system. One could argue this is simply how the business world works: survival of the fittest. However, something feels different about agriculture compared to other industries in this regard, largely because humans throughout history have lived with an intimate connection to the land that grows their food. Therefore, it’s likely that we’ve forfeited an integral part of ourselves by breaking our relationship with natural ecosystems en masse. This isn’t to say that pre-industrial agriculture was an idyllic paradise and societies should have eschewed anything resembling technological progress. Nostalgia for the “good old days” of agriculture can easily be overblown. But the fact is that politicians and industry leaders have let everyone know from the beginning that the march toward an increasingly industrial agricultural system is simply inevitable no matter how many farms are forced out of the industry. It’s simply the self-proclaimed Law of Butz: adapt or die.

Case in point, R. Douglas Hurt, a Purdue University history professor who specializes in agriculture, said in 2023 that, “Farms probably will get larger and become fewer in number in the years ahead. This is not necessarily a problem. Small-scale family farms are not more economically viable or more moral than large corporate farms, most of which are family corporations for tax purposes.” (https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2023/nov/07/joe-biden/did-americans-lose-the-farm-fact-checking-joe-bide/) Leaving aside the brushed-off assumption that large corporate farms are just as moral as small-scale family farms, there is a serious risk in food production falling in the hands of a fewer businesses. The recent COVID-19 pandemic revealed just how vulnerable the current food production, processing and transportation system is to unforeseen events. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9335023/) Bottlenecks all along the chain, particularly in the meat processing plant sector (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/business/coronavirus-meat-slaughterhouses.html), create stress points that leave consumers at higher risk of shortages on supermarket shelves. The same risks are present with the increasing monopolization of food production, particularly when considering that major disease outbreak increases as plants and animals of the same species are placed in close proximity. Of course, there are risks and rewards with every system, but the risk of placing such a basic human need in the hands of fewer individuals who live further away from their consumers is, at the very least, something to ponder.

Hearkening the spirit of Rusty Butz, Sonny Perdue, while Secretary of Agriculture in 2019, echoed Hurt’s stance when he told an audience at a dairy expo in Wisconsin that, “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out. I don’t think in America we, for any small business, we have a guaranteed income or guaranteed profitability.” Perdue went on to say that, “It’s very difficult on an economy of scale with the capital needs and all the environmental regulations and everything else today to survive milking 40, 50, or 60 or even 100 cows.” (https://www.cbsnews.com/news/agriculture-secretary-sonny-perdue-says-family-farms-might-not-survive/) Exactly. The current production model that farmers were pushed to adopt requires such a large amount of capital that farmers need to produce an enormous amount of product to justify their large capital investments to keep up with the rest of the herd. Many farms simply can’t afford to keep up the pace in that race and they have to drop out, providing more land for surviving farms to divvy up. Theoretically, then, surviving farms should be making more profit and the farming community as a whole should be performing just as well because each farm has that much more money to put into their local economies. Is that what has happened?

First, consider that farming is a business unlike any other, as president John F. Kennedy rightly pointed out.

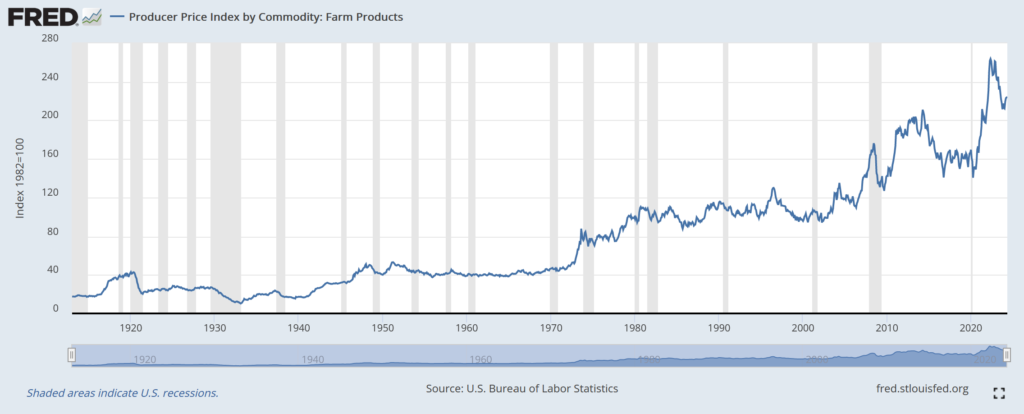

Not many other industries play a game where the rules are so tilted against them. What it boils down to is that farmers playing the commodity game are at the mercy of several variables outside of their control. COVID and Russian invasions being recent examples. Contrast that to a normal business, like the sandwich chain Subway. Remember the $5 footlong introduced in 2007? Why is that no longer around? According to journalist Kelly Corbett, “Subway’s $5 footlong sandwich promotion, which was introduced during the dawn of a recession, could not withstand rising costs, and naturally, the price had to go up.” (https://www.distractify.com/p/what-happened-to-five-dollar-footlongs) That’s how most businesses operate. They raise the price of their product when it costs more to produce it. Commodity farmers? Not so much. Farmers can’t increase the price of commodity goods, even when it costs them more to make the same amount of product. So if input prices go up, farmers and ranchers have to deal with it in ways other than raising the price of their goods. Thankfully, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data show that commodity prices have risen over time.

Unfortunately, farmers don’t put commodity prices into their bank accounts. They put net farm income into their bank accounts, and this metric varies widely year to year. In fact, at the time of writing in 2024, estimates show that farm income is likely to take the biggest hit since 2006. (https://www.farmprogress.com/farm-business/2024-farm-income-to-face-biggest-annual-decline-since-2006) One reason is inflation, even though “the relationships between inflation and commodity prices are not strong.” (https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2022/06/inflation-and-commodity-prices.html) Price is mostly determined by supply and demand. Input prices, on the other hand, are significantly correlated with general inflation, with machinery and labor following closer to inflation than feed, seed, fertilizer, and fuels. (https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/resource/2023/10/trends-in-general-inflation-and-farm-input-prices-202310/) This has spelled trouble in the cattle, hog, and broiler markets, as “prices have not kept pace with inflation over the past 30 years.” (https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/ag-and-food-statistics-charting-the-essentials/agricultural-production-and-prices/) In the grain market, “Prices could average well below the current break-even levels of $4.73 per bushel for corn and $11.06 for soybeans (see farmdoc daily, December 21, 2021). Lower prices will likely occur in the future because of above-trend yields increasing supply.” (https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2022/06/inflation-and-commodity-prices.html) Purdue University’s most recent Crop Cost and Return guide estimates the following earnings per acre for commodity grains grown in average productivity soils in the state of Indiana: Continuous corn: -$178, Rotation corn: -$79, Rotation Soybeans: -$1, Wheat: -$183 and Double Crop Soybeans: $240. (https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/paer-article/2024-purdue-crop-cost-return-guide/)

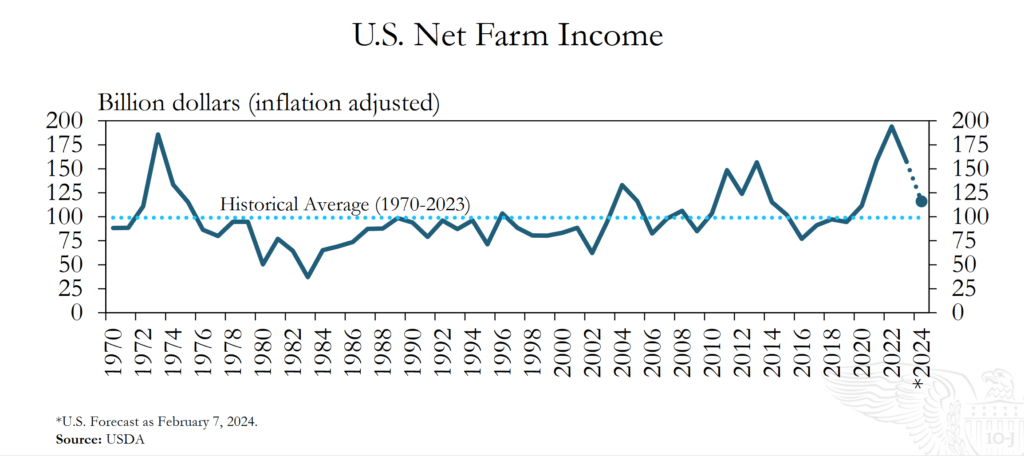

The point being made is not that 2024 is shaping up to be a rough year financially, although this is significant. The overarching point is that over the long-term the industrial agricultural system has incentivized the small fish to get eaten by the medium and large fish. Now, the conditions are right for the medium fish to get eaten by the large fish. One would think that the surviving medium farms would have been much more profitable as they swallowed the small ones, but many are still struggling to pencil in a profit year after year. This shows that focusing on producing an enormous amount of product for a gradually increasing price is not a winning strategy in commodity agriculture. Yield, pounds of animal sold and higher prices are not all of the variables in the equation of profitability. The cost of producing goods also has to be factored in before net profitability can be established. In addition, interest payments on “necessary” operating loans are an input cost that farmers of old didn’t have to contend with, so farmers of today really can’t afford a bad year or, heaven forbid, a string of bad years financially. USDA’s Economic Research Service forecast in 2022 that total farm sector debt will increase to a record high $535 billion in 2023. As a share of production expenses, interest expenses are the third largest (7.4%). Interest expenses are the fastest growing farm production expense, increasing 19.1% in 2023 and 33.2% in 2022. Fortunately, debt-to-equity ratios remain fairly low thanks to increasing land values, which represent 84% of total farm sector assets in 2024. (https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-sector-income-finances/assets-debt-and-wealth/)

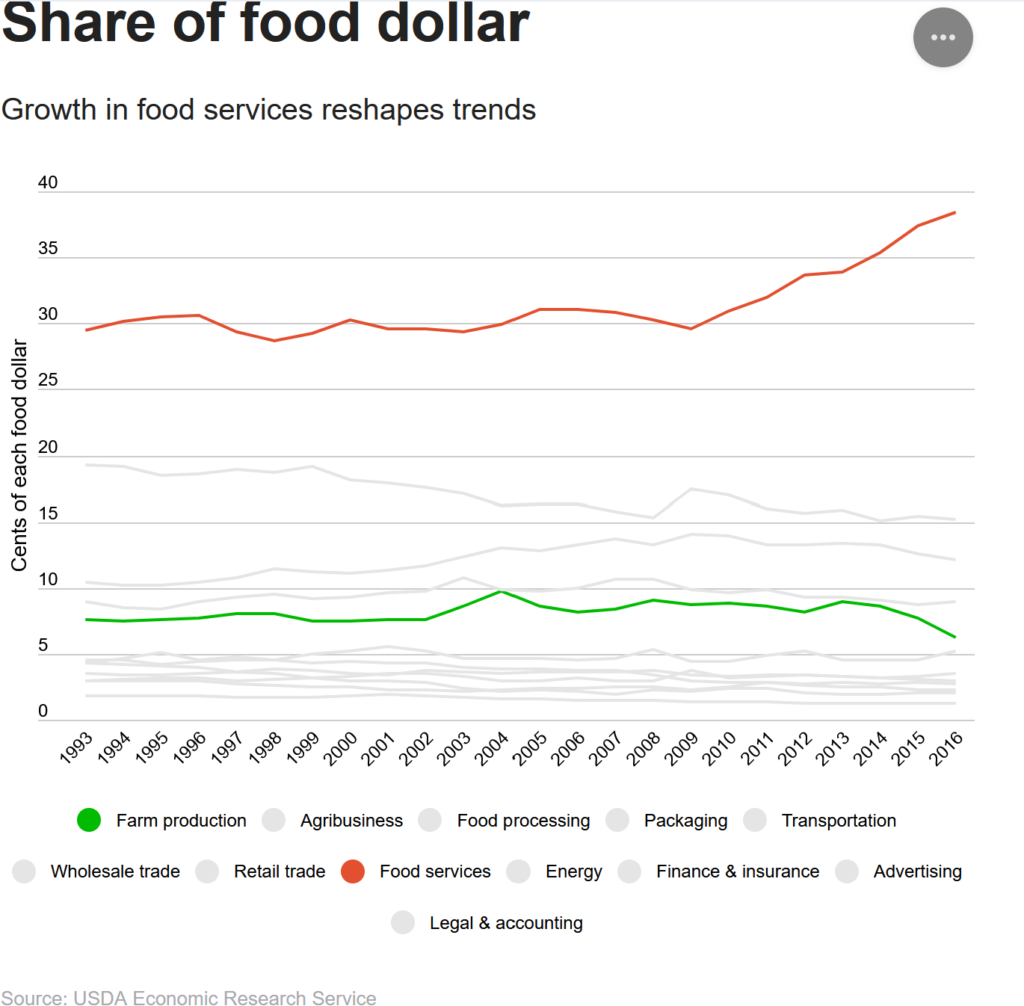

Another metric worth investigating that affects net profitability is the commodity farmer’s share of the food dollar. Commodity farmers are essentially price takers, not price makers. Sadly for them, their share of the food dollar is at an all-time low in the U.S. (https://www.agweb.com/news/business/taxes-and-finance/farm-share-us-food-dollar-hit-record-low-what-does-mean-producers) and it is also decreasing in other nations like the U.K. (https://www.sustainweb.org/reports/dec22-unpicking-food-prices/) Economists believe this is largely due to more meals eaten at restaurants and more restaurant meals delivered to homes. The graph below shows that the farmer’s share of the food dollar has been decreasing the fastest as restaurants take more of the food dollar. (https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/44825/7759_err114.pdf?v=0) In general, the more hands that touch a product between harvest and consumer, the less of the food dollar a farmer or rancher will see.

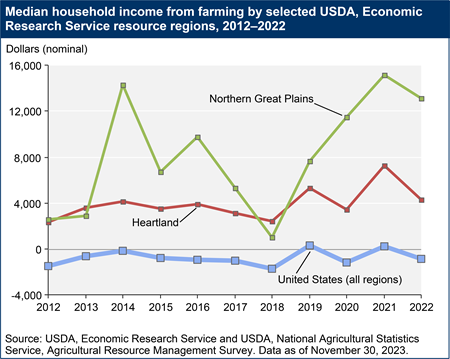

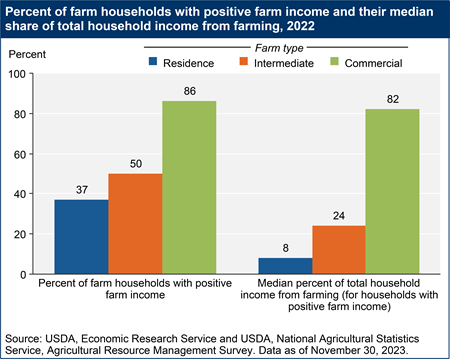

Overall, U.S. net farm income has remained relatively static in the period from 1970-2024. This in spite of the fact that there are roughly 350,000 fewer farms in 2024 than in 1970. Average net profitability per farm is incredibly difficult to calculate and average out because farms vary in many ways, including farm size, product raised and location. With that said, the median household income from farming in the United States from 2012-2022 was at or below $0 each year. (see graph below) This is likely biased toward the lower end by the fact that there are so many farm are small and hobby farms, and these farms don’t make money on average. Nevertheless, off-farm income is the main source of income for many farming families, big and small.

A more complete breakdown of median farm household income can be found from the USDA here.

Individuals that choose to stay in rural communities face many of the same challenges as their urban neighbors. However, outcomes are often worse for rural citizens, as in the case of public health. Dr. Macarena Garcia, a senior health scientist in the CDC’s Office of Rural Health, points out that, “There is a well-described, rural-urban divide in the United States, where rural residents tend to be sicker and poorer and to have worse health outcomes than do their non-rural peers.” (https://abcnews.go.com/Health/rural-americans-higher-risk-early-death-urbanites-cdc/story?id=109742216) One reason for this is that rural areas are often lacking in various resources, which purely comes down to available money. (https://time.com/6980243/classism-rural-america-essay/) Local funding for health and social services is determined primarily by an area’s overall wealth, tax base, and fiscal policies, and many rural communities have a low and declining tax base. (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/109114210002800402) Specifically concerning agricultural workers, long-term exposure to chemicals like pesticides is associated with various negative health outcomes, such as an increased risk of brain cancer (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8431399/), Parkinson’s Disease (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1059924X.2017.1317684), and prostate cancer (https://www.sciencenews.org/article/farm-harm-ag-chemicals-may-cause-prostate-cancer).

The two-decade increase in opioid mortality is also concerning because it hit rural communities especially hard. Interestingly, opiate deaths have corresponded with significant economic stressors in some rural areas, as rural labor markets are less diversified than urban ones. This makes them more vulnerable to economic shifts when downturns occur. (https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/opioid-crisis-rural-small-town-america) Silently, another crisis has infected rural communities: the mental health crisis. Farmers have suicide rates much higher than the general population, with elevated mental health symptoms and high stress levels. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10896109/) One report claims that farmers are 3.5 times more likely to commit suicide than the general population. (https://www.agweb.com/news/business/health/startling-reality-rate-suicide-among-farmers-35-times-higher-general) Farmer suicide rates are so high that the USDA is giving mental health training to professionals working in farming communities. (https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2024/06/15/farmer-suicide-usda-mental-health-training/74076743007/) Family therapist David Brown, leader of one of the mental health sessions, explained some of the unique challenges that farmers face to the audience. He noted that, “current owners feel that if they fail, they would be letting down their grandparents, parents, children, and grandchildren.” He also said that, “farmers’ fate hinges on factors out of their control. Will the weather be favorable? Will world events cause prices to soar or crash? Will political conflicts spark changes in federal agricultural support programs? Will a farmer suffer an injury or illness that makes them unable to perform critical chores?” (https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2024/06/15/farmer-suicide-usda-mental-health-training/74076743007/) Tethering profitability to the increasingly unpredictable world is a risky way of doing business, but it’s the model that farmers and ranchers were pushed to adopt. Unfortunately, too many of them lose hope that external factors will improve and their situation will turn around.

All of these factors, and likely many others, add up to a difference in life expectancy as much as 5 years higher, on average, between wealthy and poor, mostly rural (https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2020/may/extreme-poverty-counties-found-solely-in-rural-areas-in-2018/), counties in the United States. (https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305728) Health and wellness, it turns out, might just depend more on a person’s zip code than their genetic code. (https://hms.harvard.edu/news/zip-code-or-genetic-code) Yet, the disparity in rural health is almost paradoxical. One would think rural citizens would have cleaner air, cleaner water and better access to fresh fruits, vegetables, milk and meat seeing as they don’t live in crowded concrete jungles. They live closer to natural landscapes. And yet, a large portion of rural America is a food desert, meaning there is a lack of nutritious foods in the very places blessed with some of the most fertile soils in the world. And yet, places like “Cancer Alley” exist in rural Louisiana. (https://www.businessinsider.com/louisiana-cancer-alley-photos-oil-refineries-chemicals-pollution-2019-11?op=1) And yet, farmers, who get to work with nature and all its mysteries and wonders, are miserable to the point of suicide.

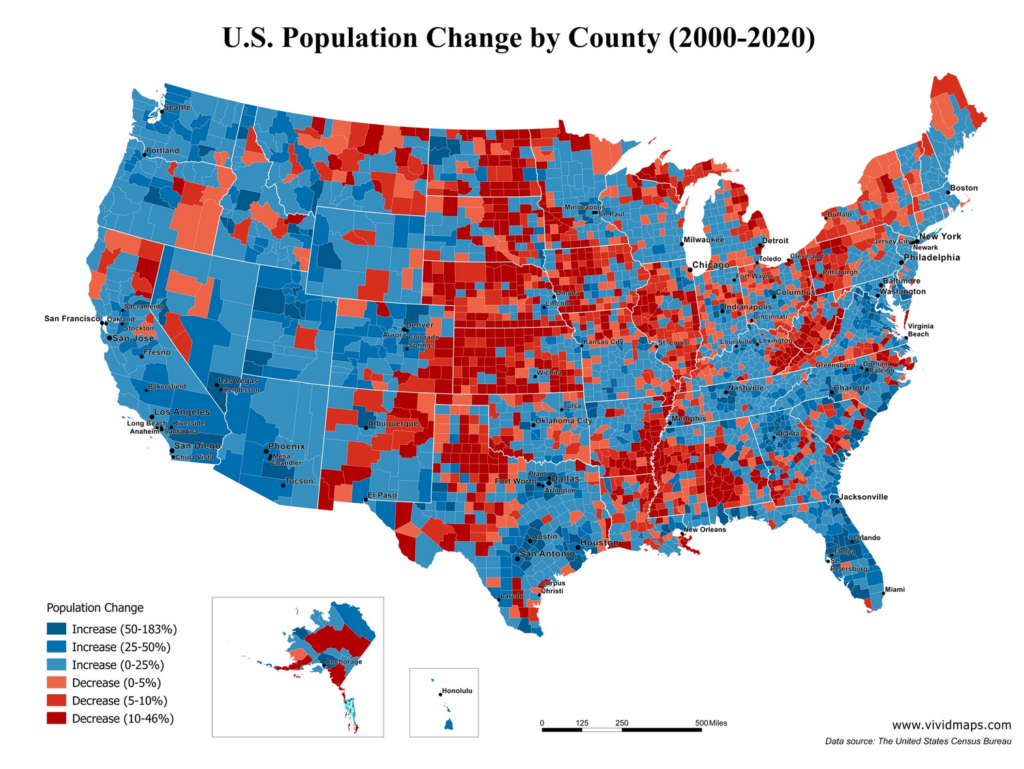

Obviously, the industrialization of agriculture, and society as a whole, has brought many positives to rural America. Life expectancy has risen 25 years from 1920-2020. (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1040079/life-expectancy-united-states-all-time/) Most towns have a hospital, a grocery store and K-12 schoolhouses. Most rural households have cars, electricity, indoor plumbing, refrigerators, Wi-Fi, satellite TV and all the rest of the amenities that city folk enjoy. Most would say this is a good thing. Wendell Berry might not be so quick to take that stance… but most people would. Even so, most rural towns and counties across the nation are declining economically, causing young people to move to urban and suburban towns in search of better employment and social opportunities. In addition, industrial, commodity agriculture doesn’t appear to be an attractive occupation for most young people today.

Agricultural Output Businesses (Supermarkets, Restaurants, Any Middleman)

Cargill CEO after buying third largest chicken producer in U.S.: Small suppliers cannot supply food cheaply

Also observed is a widening disparity among the income of farmers and the escalating concentration of agribusiness—industries involved with manufacture, processing, and distribution of farm products—into fewer and fewer hands. Market competition is limited and farmers have little control over prices of their goods, and they continue to receive a smaller and smaller portion of consumer dollars spent on agricultural products. Economically, it is very difficult for potential farmers to enter the business today because of the high cost of doing business.” (https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/envirobiology/chapter/9-3-conventional-agriculture/) Some say that farming is the only industry you can’t afford to get into or out of.

Over the course of industrialization, markets for food and agricultural products have become increasingly concentrated. In the U.S. beef slaughtering and processing industry, for example, the four largest companies earn 82 percent of the sales.19 In the supermarket industry, four companies earn at least 42 percent of the sales.20

(https://foodsystemprimer.org/production/industrialization-of-agriculture)

In the supermarket industry, four companies earn at least 42 percent of the sales. (Jameset al., 2013)

Increased dairy cow output and advances in dairy farm technology and management have led to a sharp reduction in the number of dairy farms. Annual losses averaged 96,000 operations in the late 1960s and 37,000 in the 1970s. In recent years (2010), the annual drop in dairy farm operations has slowed to about 2,000 to 5,000 farms per year. (USDA, 2010)

Conditions of farm workers, seasonal, meat factories, etc.

What does market concentration mean for farmers and consumers? In some cases, market concentration can lower prices for consumers and increase sales. On the other hand, with fewer competitors in a concentrated market, dominant companies may gain greater power to influence prices in their favor. They may also dictate how foods are produced, leaving farmers with little choice over how to grow crops or raise animals. Many highly concentrated corporations also have a strong presence in government agencies, where they can influence policies in their favor. (Johns Hopkins, 2014)

The vast majority of U.S. poultry and pork products comes from facilities that each produce over 200,000 chickens or 5,000 pigs in a single year, while most egg-laying hens are confined in facilities that house over 100,000 birds at a time. (Johns Hopkins, 2014)

vSmaller, more local meat processing plants are closing nationwide, leaving farmers with fewer options to process meat.

“Mergers mean that farmers have fewer and fewer choices for buying and selling, while vertical integration has meant that big agribusinesses face less competition throughout the chain and thus capture more and more of the profits,” Warren wrote March 27. “The result is that farmers are getting a record-low amount of every dollar Americans spend on food, food prices aren’t going down, and agribusiness CEOs and other corporate executives are raking it in.” (https://www.politifact.com/factchecks/2019/apr/04/elizabeth-warren/why-do-farmers-get-so-little-our-food-dollars-us/)

They’re just looking out for us, just like Kellogg’s CEO telling cash-strapped Americans to eat more cereal for breakfast. (https://www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/kellogg-ceo-cereal-dinner-save-money-2024-2)

Environment

The water, energy, and nutrients required to raise crops and livestock can’t come out of thin air. They’ve got to come from somewhere, and that somewhere is the natural resource base of the planet. Industrialization has done an excellent job of designing systems that divert more matter and energy from the natural resource base into agricultural production, which has greatly increased food production over the most recent centuries. This mass manipulation of the environment has been a boon for providing more calories to the human population, but what have been the effects on other species and the planet itself?

An important fact to remember is that humans have been shaping and reshaping the natural environment for millennia. One reason is that many ancient societies relied heavily on the plow to prepare the ground and control weeds, which caused widespread soil erosion. After all, the present-day nations of Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Syria, Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Cyprus were once considered the Fertile Crescent. Not so today, and the way societies treated their soil is likely a leading contributor to the degradation. David Montgomery’s “Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations” is a must read on the topic, as he details how soil erosion influenced the fates of Mesopotamia, Ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, China, European colonialism, Central America, and necessitated the American push westward. Overall, there is about half of the green and photosynthesizing land cover today as there was 8,000 years ago, meaning that 5 billion hectares (12.4 billion acres) have become desert in 8,000 years. (https://www.ecofarmingdaily.com/supporting-the-soil-carbon-sponge/) Agriculture is certainly not the only reason for large-scale desertification of the planet, but it has no doubt played an integral role in the de-greening of the planet.

Today, land degradation is accelerating, reaching 30 to 35 times the historical rate, according to the United Nations. This degradation is caused by a number of factors, including urbanization, mining, farming, and ranching. (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/desertification) One reason agriculture has accelerated land degradation is that the size and power of equipment has dramatically increased in recent decades. Traditionally, animal-drawn plows knifed into the soil a few inches, but today’s multi-ton tractors are able to pull plows that move over a foot of soil at a furious pace. Another reason is that an increasing world population demands more food, firewood and wood building materials, which has caused an acceleration of the loss of native climax communities around the planet. Since the end of the last ice age around 11,700 years ago, the world has lost around one-third of its forests. Two billion hectares (4.9 billion acres) of forest have been transitioned into agricultural land and/or harvested for fuel and building material. To put into perspective the accelerating rate of deforestation, consider that half of the global forest loss occurred between 8,000 BC and 1900. The other half was lost from 1900 to today. (https://ourworldindata.org/deforestation) Forests are extremely important for the health of the planet for a plethora of reasons, including their ability to positively impact the efficiency of the planet’s energy and water cycles. Similarly, a large portion of grasslands, which cover more than 70% of the planet’s land mass, have transitioned into cropland, development or desert in the past few millennia. In fact, nearly half of all temperate grasslands and 16 percent of tropical grasslands have been converted to agricultural or industrial uses and only one percent of the original tallgrass prairie exists today. (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/grassland-threats)

Turning grasslands and forests into agricultural land might sound like a tit for tat trade, but ecologic performance decreases after the transition, particularly in land managed conventionally with set-stock grazing, monoculture cropping and high use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers. Take cropping for instance. The most productive land is usually transitioned into cropland first, while more marginal land is used for grazing. This means that each additional acre of cropland transitioned is likely to be less and less productive as time goes on because the most productive land around the planet has already been used as cropland for centuries. For example, in the U.S. from 2008-2016, croplands expanded at a rate of over one million acres per year, and 69.5% of new cropland areas produced yields below the national average, with a mean yield deficit of 6.5%. Grasslands, including those used for pasture and hay, constituted 88% of the land converted to crop production across the US. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-18045-z) Of course, humanity needs to produce food for itself, but food production is not happening in a vacuum, meaning there are many other variables in the equation for our survival. Agricultural production, and humankind as a whole, also relies on the trillions of living beings on the planet to purify freshwater, cycle nutrients efficiently, pollinate crops and a whole host of other crucial services. Therefore, undermining microbial, plant and animal communities in order to produce in the short-term is a recipe for decreasing efficiency in the long-term. This is why the term “biodiversity” is thrown around so much these days. Earth is a solar-capturing, self-perpetuating biological system only because the abundance and diversity of life works together. Simplifying landscapes runs the risk of reducing this biodiversity, as well as the resilience and efficiency of ecosystems that our species needs to survive into the future.

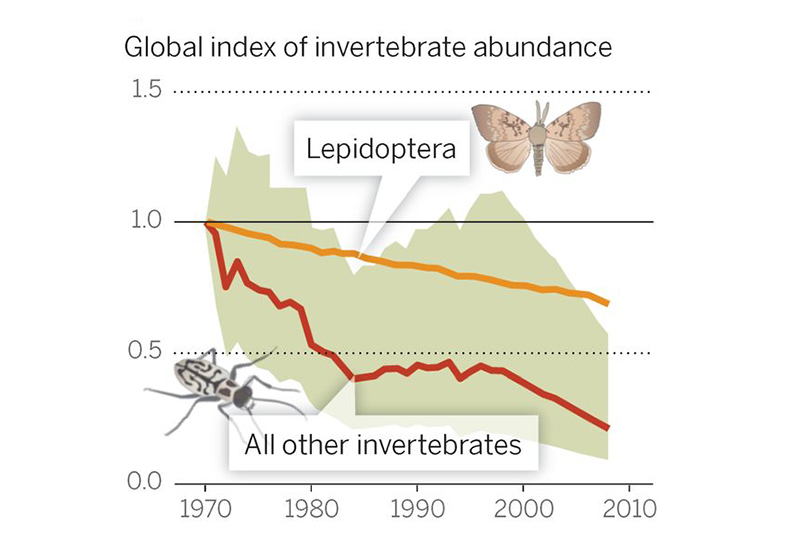

As one might imagine, biodiversity loss does appear to be accelerating around the world. The global rate of species extinction today is orders of magnitude higher than the average rate over the past 10 million years. Land and sea use change are often cited as the dominant direct driver of recent biodiversity loss worldwide (https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm9982), with the global food system as the primary cause of these land use change patterns. (Benton et al., 2021) The effects on biodiversity appear to vary by species, but the common sense point to remember is that species need food and habitat to survive in a landscape. Take away one or both, and that species will struggle to survive as well as it used to. For example, one study found that, “abundance and richness [of insects] were reduced by 7% and 5%, respectively, in which high levels (75% cover) of natural habitat are available, compared with reductions of 63% and 61% in places where less natural habitat is present (25% cover).” (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-022-04644-x) Another report from Cambridge University found that, “The bees, butterflies, wasps, beetles, bats, flies and hummingbirds that distribute pollen, vital for the reproduction of over 75% of food crops and flowering plants appear to be a subset of insect hit particularly hard by land use change and pesticide applications.” (https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/pollinatorsriskindex) Although these studies may be true, the “insect apocalypse” widely reported may be more complex than once thought, as net insect populations may remain relatively constant, especially in North American studies (https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10301082). What does appear to change are the diversity and turnover rates of some species compared to others. Every place on the planet is different and reacts to management changes in unique ways. This illustrates that making blanket statements for the whole planet is very difficult, even though large-scale patterns may emerge from the data.

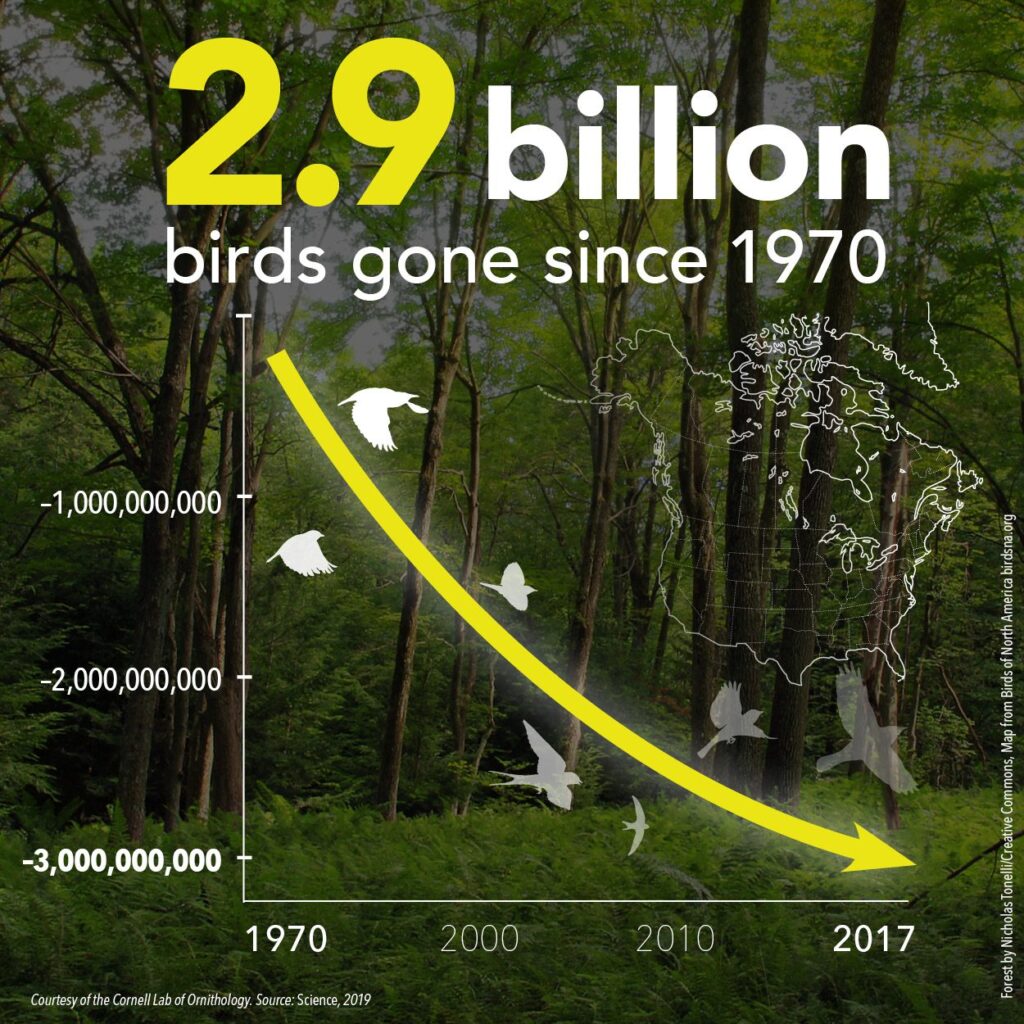

Birds are another class of species that receive a lot of press concerning their population decline. It makes sense on the surface that bird populations would be in decline if insect populations are in decline, as they rely upon insects as a major food source. This appears to be the case, as BirdLife International, a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats, details in their State of the World’s Birds Report for 2022 that 49% of the planet’s birds are in decline. Their research shows that agricultural expansion and intensification is currently impacting 1,026 species (73%) of globally threatened bird species worldwide. These threats drive declines in bird populations through a variety of mechanisms. The most important mechanism driving population decline is habitat conversion and degradation (1,336 species, 95%), while other mechanisms include direct mortality of individuals (862 species, 61%) and indirectly effects, including reduced reproductive success (510 species, 36%) or increased competition (134 species, 10%). (https://www.birdlife.org/papers-reports/state-of-the-worlds-birds-2022/) In North America, grassland and farmland birds have been experiencing severe declines in recent decades. In this case, pesticides and harvesting/mowing are reported as among the most influential factors related to their decline. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016788091730525X?pes=vor) Birds, it turns out, might be the literal canaries in the coal mine indicating that ecosystem function is in decline on agricultural land.

No farmer or rancher intends to harm biodiversity by the way they operate. In fact, most land managers love their land and want to make it healthier over time. Unfortunately, evidence is mounting that modern, conventional methods adopted in recent centuries to produce more calories, fiber and fuel have caused unintended negative consequences affecting biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Unintended consequences are not the only cause of biodiversity loss, however. Humans have also been intentionally reducing diversity through breeding and selection. Consider that more than 20,000 species of edible plants are available across the globe, but only fifteen species provide 90% of the food requirement of the world’s population today. Just three crops, (rice, wheat and maize) provide a whopping 60% of the world population’s energy intake. (http://www.fao.org/3/u8480e/u8480e07.htm). (Sreenivaulu & Fernie, 2022) Bananas are a great example of this simplification, as 50% of bananas grown globally, and 99% of exported bananas, are of one variety, the Cavendish banana, due to its ability to resist bruising and high yields, despite there existing around 1,000 different varieties of bananas. The same story goes for livestock. I.R. Bowler wrote in 1986 that, “The first half of the 20th century marks an era of great breed extinction in Europe with breed losses amounting up to 50% as a result of the expansion of industrialization processes in agriculture, especially in the decades immediately after the Second World War (https://www.jstor.org/stable/40571039).” (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0921800921001750) Breed loss, the FAO writes, is considered one of the greatest threats to animal husbandry, agrobiodiversity and biodiversity (FAO, 2015), raising the risk of major unpredictable problems and challenges in the future.

What exactly is the problem with relying on a few ultra-productive varieties of crops and breeds of livestock? Just as species diversity promotes resilience in a landscape, genetic diversity promotes species and community resilience. (https://www.nature.com/articles/s44185-023-00022-6) This is largely because a group of individuals with a very similar set of genes is extremely susceptible to pest and pathogen attack. Imagine a thousand homes with one type of lock on their front door. A burglar is able to enter each house once they get the right key, whereas they would have to find a thousand different keys if there were a thousand different kinds of locks. Consider the Cavendish banana once again. The Gros Michel banana was once the world’s most produced banana until a fungal disease called Panama disease, a form of banana wilt, ravaged the species. Producers switched to the Cavendish banana due to its resistance to banana wilt, along with its superior yield and shipping ability. Global banana infrastructure was reshaped to fit the Cavendish. The problem was solved and the day was saved. That is, until something adapted to attack the Cavendish. A new strain of Panama disease, Tropical Race 4, now has the ability to infect Cavendish bananas, leaving the banana industry reeling once again. The nation of Colombia went so far as to announce a national declaration of emergency in August of 2019.

Additional cautionary tales of susceptibility include the Irish potato famine of the mid-19th century caused by the fungus phytophthora infestans, as well as citrus greening, a bacterial infection ravaging the Florida orange industry. The bulk of U.S. orange crops consist of just three main varieties: the Washington Navel, the Valencia, and the Hamlin, all chosen for their ability to ship long distances and easily make juice. (https://www.producebluebook.com/know-your-produce-commodity/oranges/)

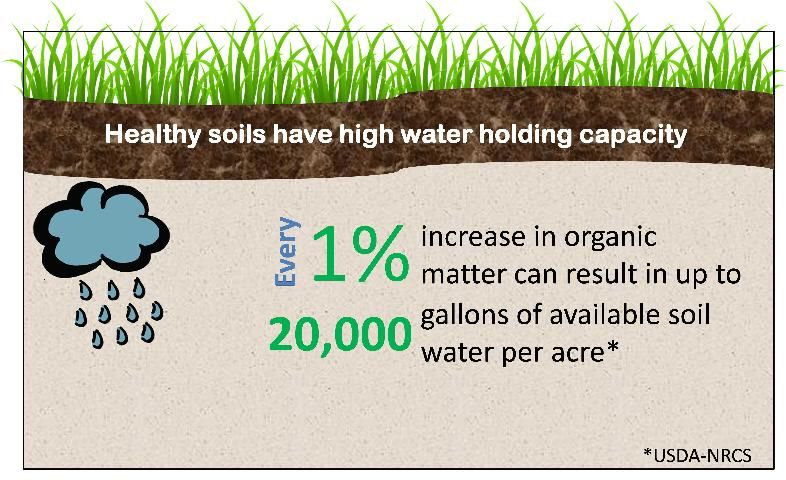

It’s often the case that we macroscopic, above-ground creatures have a natural bias toward the large, macroscopic happenings around us, but the loss of microscopic, underground diversity is just as worthy of our attention. As it turns out, reports of declining soil biodiversity and the simplification of soil food webs due to intensive agriculture abound. One group found that the number of feeding groups, total biomass of the soil food web, and biomass of the fungal, bacterial, and root energy channel [which consists of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), root-feeding fauna, and their predators] were all lower under an intensive wheat rotation and extensive crop rotation relative to grassland. (de Vries et al., 2013) Another team of researchers write that, “land use intensification reduced the complexity in the soil food webs, as well as the community-weighted mean body mass of soil fauna. In all regions across Europe, species richness of earthworms, collembolans and oribatid mites was negatively affected by increased land use intensity.” (Tsiafouli et al.) Finally, it may come as a surprise but even fertilization can cause issues. Steven Heisey and his colleagues reported in 2022 that “fertilization with urea did not significantly alter the structure of soil microbial communities compared to the control but reduced network complexity and altered hub taxa.” (Heisey et al.) Network connectivity and complexity are crucial features of an ecosystem that is resistant to takeovers by one species. (https://www.ecdysis.bio/_files/ugd/49b043_26e90d07f26c4304b7b14f8a10de69b3.pdf) With that said, research shows that some fertilization may decrease soil organic matter losses (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00374-017-1194-0), so the truth is likely not as black-and-white as “fertilizers = bad”.

It will be discussed in depth shortly, but the significant loss of soil organic carbon since the adoption of industrial agriculture is less debatable and further troubling evidence of, and simultaneously a reason for, underground biodiversity loss. Farmers and ranchers simply can’t afford the services of their underground employees to slow down any more than they already have. If so, producers will miss out on the soil community’s ability to suppress disease, which means more pesticide purchases. Less diversity also leads to less efficient nutrient cycling, meaning more fertilizer purchases. The topic of diversity, resilience and agriculture’s role in promoting both deserves much more space than is provided here, so check out these articles about the all-important ecosystem function called community dynamics to dive deeper. Part 1 can be viewed here, while part 2 can be found here. In short, implementing the six principles of soil health and three rules of adaptive stewardship builds biodiversity and resilience, while indiscriminate use of industrial methods tends to deteriorate both.

In summation, industrial agricultural practices promote land degradation and biodiversity loss. This is very troubling considering that humans rely so heavily on the land and the trillions of organisms on the planet for their survival. But what about another ubiquitous element of life on this planet? How has industrial agriculture affected water cycling and water quality? As it turns out, water quality and biodiversity are intimately linked, as about one-third of the reduction in global biodiversity is estimated to be a consequence of the degradation of freshwater ecosystems mainly due to pollution of water resources and aquatic ecosystems. (United Nations, nd) While it’s easy to envision water pollution as a pipe spewing factory waste into a lake or a bunch of trash floating in the ocean, agricultural pollution of the water is often more subtle, but can be just as harmful. Farmers and ranchers can either manage their soils in such a way that purifies the water leaving their land or pollutes it. Healthy soils are ultimately the linchpin in determining which of the two paths water quality will take. Proponents of permaculture, including author Mark Shepard in his book Water for Any Farm, often say that the job of farmers and ranchers is to manage the land such that soil can “Slow, Spread and Soak” water. Therefore, the first job of soil is to slow down water during rain or irrigation events. Imagine how quickly water descends a rocky slope during a rainfall event. This water quickly finds the lowest point in the landscape due to gravity, which can cause ponding and flooding. The same process is carried out when soils are unable to infiltrate water during heavy rainfall or irrigation events. Rivers and streams swell almost immediately following such events because the soil infiltrates it slower than it can descend to the lowest point. So step number one to managing water is to give it time to actually infiltrate into the soil profile.